Howl’s Moving Castle, Ponyo & The Wind Rises

This is Part 5 of Adam’s series reviewing the films of Studio Ghibli. You can find Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 & Part 4 by using the hyperlinks.

Hayao Miyazaki’s films for Studio Ghibli are each so different from the others, yet so very similar in ways I find difficult to express. Continually they return to themes of acceptance (both outwardly and inwardly), of loss, of the futility of conflict, of the power of the connections between people and the world. How important it is for us to have compassion, to encourage, to be kind. I’ve found that after each one, I’ve needed to take a few minutes after letting the credits roll to the end, just to sit with how I feel. To reflect on the film as it ended and as a whole. Now, I don’t have much to say about Howl’s Moving Castle. It was enjoyable with some interesting characters and designs with that central message about accepting yourself.

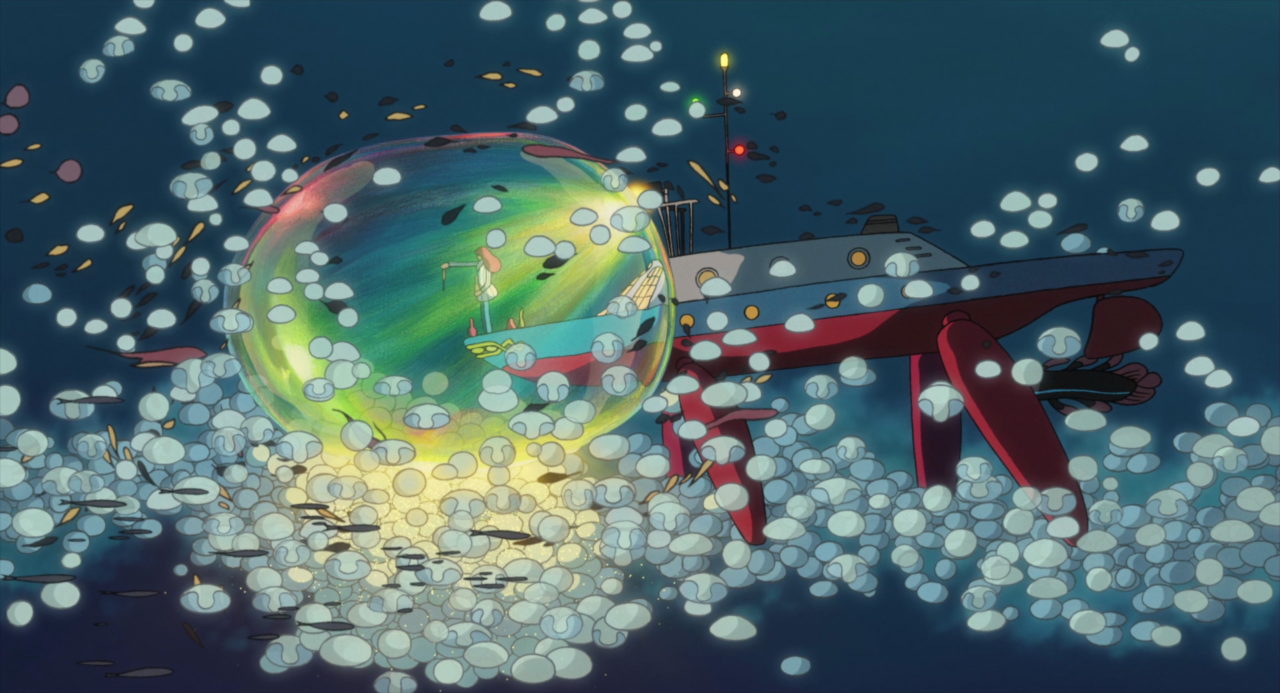

Ponyo on the other hand is, by far, my least favourite Ghibli film. It started off strongly. The opening scenes taking place under the waves had me intrigued. Depicting a fascinating underwater world where some sort of magic was at play. This wasn’t really the focus of the film, instead it focused on telling a rather innocent childhood love story about a small boy who fell in love with a magical “goldfish”. Unfortunately, I didn’t gel with the characters. I’ve expressed before that I’ve found the inclusion of “love” in these films to be the weakest element and I feel that is true here as well. It isn’t logically flawed, it isn’t entirely unfeasible, it’s just the least interesting aspect of it. To simplify the whole thing down to a question of whether a child’s love is true.

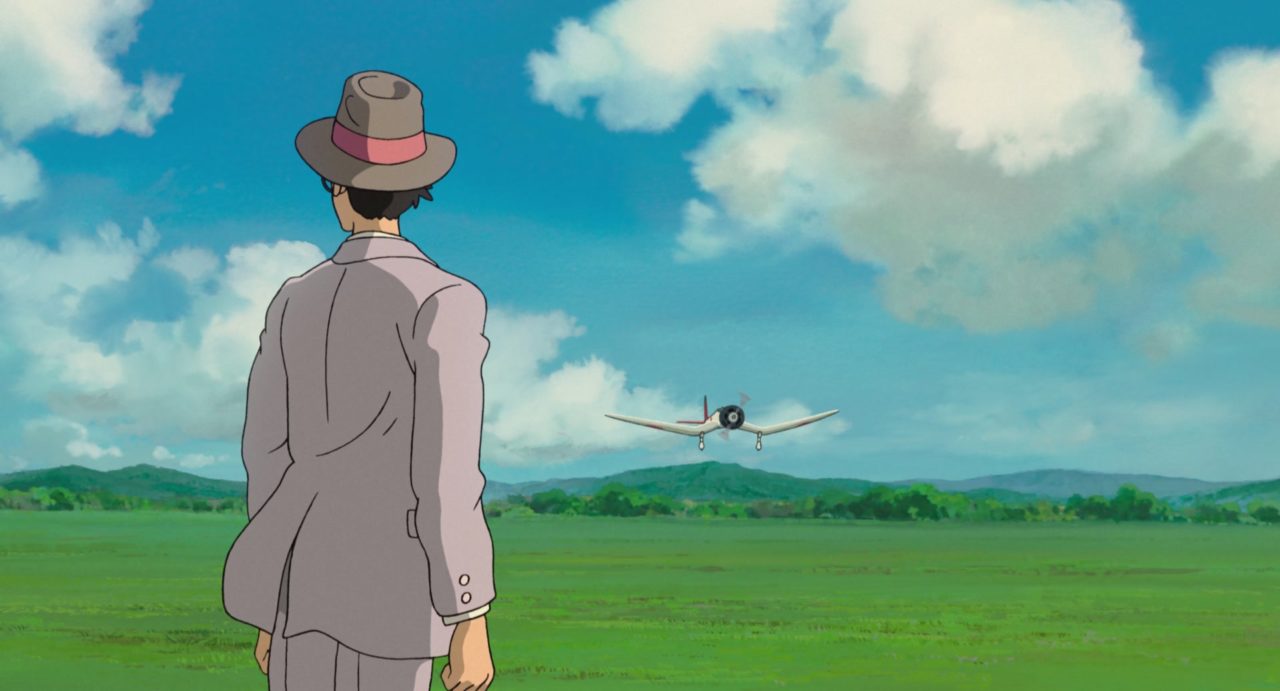

The Wind Rises proves to be one of the most complex emotionally and intellectually. Set in Imperial Japan, it tells the story of the man who would go on to design one of the most iconic, or indeed infamous, aeroplanes of WW2; The Mitsubishi A6M aka The Zero. It isn’t a straight biopic however as it incorporates many elements of a novel published in 1937 by Tatsuo Hori called The Wind Has Risen. In this fictionalised telling, Jiro Horikoshi is presented as being inspired by dreams to design and create beautiful aeroplanes while the reality of what they will be used for refuses to be ignored.

I have sympathy for that point of view. It’s one that is backed up historically through diaries and testimonials from other such figures, so isn’t unique to the Jiro Horikoshi as presented in the film by Hayao Miyazaki. When looked at in isolation, these creations can be truly beautiful. The sleek curves, the profile, the innovative solutions that solve problems. To label the Zero beautiful is as true as when doing so for the Spitfire. In engineering terms these were cutting edge, innovative designs that would redefine what was possible in aeronautical engineering. There is an innate beauty to an elegant solution to a complex problem. Dreams of an ideal world of perfect creations where everything is clear and straightforward.

But.

You simply cannot escape what they will be used for. Reality is not a dream. It is not filled with perfect creations crafted purely for the beauty of their forms or their designs. It is filled with horrors too. The real nature of the time always stalks the background. It is subtle at times, a closed bank references The Great Depression, a terrible economic crisis of the 1920’s that left millions across the world destitute or worse. “The Shanghai Incident” of 1932, an omen of what was to come, appears in a newspaper headline used as packing material in a parcel. Even in the dreams the death and destruction that war brings cannot be avoided entirely. The cruelty of reality overtly affects the dreamer Jiro when he falls in love with a girl who has TB. This element of the film comes from the novel and I think works excellently as part of the narrative. It’s truly heartbreaking.

I am quite familiar with the history of World War 2 having watched more than my fair share of documentaries on it. It was without question a horrendous time. Millions died in battle, millions more in air raids and millions more again in famines. Yet the technological advances made during those years would go on to shape the world we live in now. Werner Von Braun who helped design the V-2 rockets that were used to attack London would go on to be the chief architect of the Saturn V rockets that propelled the Apollo missions that put humans on the moon. Reality is not as clear cut as we might wish in our dreams.

That complexity makes for a compelling film.

Thank you for reading my review series on Studio Ghibli. I’ve gone through all of the films, in order, that were written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. It has been an incredible journey, I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did. Let me know which film is your favourite and get in touch with some of your thoughts too. I do intend to watch and review all the films from Studio Ghibli by the other directors but I think I’ll take a bit of a break before I do.

Many of Studio Ghibli’s films are currently available on Netflix (UK). Do watch them while you can, if you haven’t already.

[…] 7 of a series of reviews, looking at Studio Ghibli‘s films. You can find Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 & 6, which look at Hayao Miyazaki’s, Yoshifumi Kondō’s & Gorō […]