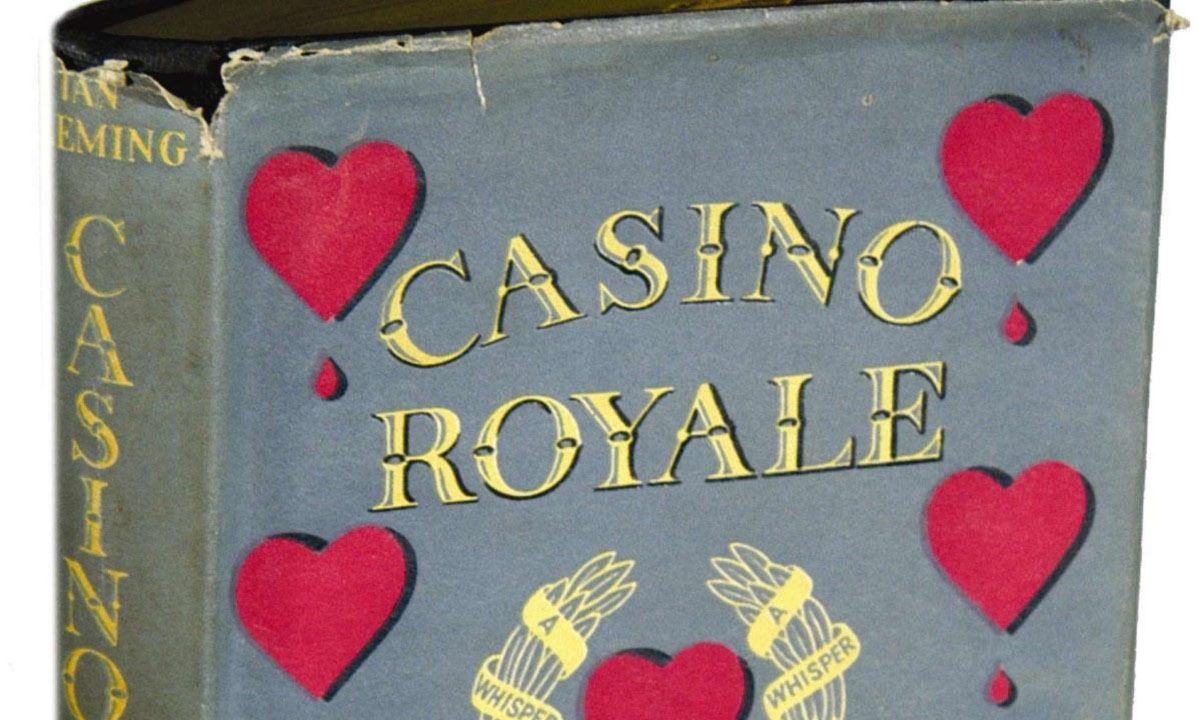

‘In medias res’ openings are often used to bypass exposition and skip straight to the action, picking up the narrative already in motion and within a flurry of excitement. Ian Fleming uses the technique in Casino Royale – the first James Bond novel – but launches the reader into anything but furor. I’ve loved the Bond films for as long as I can remember. The action; the gadgets; the maniacal villains; the whole formula. Yet I have never read an Ian Fleming James Bond book until now, finally deciding to go to the source now that we’re in a lengthy break between films. It wasn’t what I was expecting. Despite in medias res, the book doesn’t open with a gunfight or car chase but instead with Bond walking through a casino. Yet not in a charming, suave manner, delighting in vices. He’s thinking about how draining the atmosphere of such a place is. In fact, the opening chapter and our introduction to Bond is all about how incredibly tired he is as he retreats to his hotel room to sleep.

Fleming’s Bond and the world he inhabits is one of bureaucracy. A world the writer knew well considering his own experiences as an intelligence officer. We soon flashback to M giving Bond the assignment that leads him to the titular casino. His mission is to bankrupt the SMERSH paymaster Le Chiffre in a game of Chemin de far, which would result in the villain being targeted by his own people after he used their money for poor investments. We the reader receive the information on Le Chiffre and the plan to stop him the same way the characters do: official documents and memorandums, Casino Royale becoming an epistolary novel for a few pages.

Fleming’s Bond and the world he inhabits is one of bureaucracy. A world the writer knew well considering his own experiences as an intelligence officer. We soon flashback to M giving Bond the assignment that leads him to the titular casino. His mission is to bankrupt the SMERSH paymaster Le Chiffre in a game of Chemin de far, which would result in the villain being targeted by his own people after he used their money for poor investments. We the reader receive the information on Le Chiffre and the plan to stop him the same way the characters do: official documents and memorandums, Casino Royale becoming an epistolary novel for a few pages.

Fleming is clearly fully aware that this is an easy way to include exposition and create a sense of realism, but is also more than a little stale. Therefore, the memorandum is oddly spicily written for an internal document from the stuffy rooms of the Intelligence Service. M notices this and calls out the writer in a funny moment, “What the hell does this word mean?” Fleming recognises that the realistic world he wants to convey, and the fact that he’s writing a novel that has to hit several entertaining and pulpy fictional notes, can often be in conflict and so balances them here with an almost meta joke, which was most unexpected. Using such documents is an efficient way to insert exposition which otherwise could easily clog chapter-after-chapter at the front end of the book. That’s the word I would use to describe both Bond as an agent and Fleming as a writer: Efficient. Ruthlessly so.

Casino Royale has very little dialogue and Fleming will often just detail what was discussed between characters rather make the reader privy to the conversation itself. “The directors hoped that he would be playing again that evening. Bond gave an evasive reply”. While this often works in the novel’s favour and maintains a punchy pace for the barely 200-page paperback, it occasionally feels as if Fleming is just impatient and wants to get on with things, sacrificing any character whose thoughts he can’t type. Anyone but Bond. Several characters aren’t even offered names or descriptions. “Head of S” speaks to his “Number Two”. Everything is matter-of-fact and portrayed sharply. Despite the globetrotting and lifestyle, there are very few indulgent and lavish descriptions of Bond’s life and surroundings. Just the information needed for the thrills. Except when it comes to food, that is. And women.

Casino Royale has very little dialogue and Fleming will often just detail what was discussed between characters rather make the reader privy to the conversation itself. “The directors hoped that he would be playing again that evening. Bond gave an evasive reply”. While this often works in the novel’s favour and maintains a punchy pace for the barely 200-page paperback, it occasionally feels as if Fleming is just impatient and wants to get on with things, sacrificing any character whose thoughts he can’t type. Anyone but Bond. Several characters aren’t even offered names or descriptions. “Head of S” speaks to his “Number Two”. Everything is matter-of-fact and portrayed sharply. Despite the globetrotting and lifestyle, there are very few indulgent and lavish descriptions of Bond’s life and surroundings. Just the information needed for the thrills. Except when it comes to food, that is. And women.

“I take a ridiculous pleasure in what I eat and drink. It’s very pernickety and old-maidish really.” That confession is still something of an understatement from Bond. It seems as if writing the ultimate spy fiction was but one purpose of Fleming penning the adventures of James Bond. The other was to have an outlet for long passages detailing not only what food Bond likes but also precisely how he likes it. It’s clear the character of James Bond is something of a writer surrogate and Fleming wants the world to know just how crisp he likes his bacon. He writes an Alan Partridge-esque review of each meal he consumes, describing in feverish detail how a sausage can be used as a breakwater to stop beans mixing with egg.

Second only to breakfast, it’s the women of Bond’s world who are described most heavily from head to toe, lingering in some places longer than others. James is assisted on his mission to the South of France by French agent Rene Mathis, American Felix Leiter, and fellow Brit Vesper Lynd. Before he sets eyes on her, Bond, to put it mildly, is displeased with having to work with a woman on the case. “Women were for recreation. On a job, they got in the way and fogged things up with sex and hurt feelings and all the emotional baggage they carried around. One had to look out for them and take care of them. Why the hell couldn’t they stay at home and mind their pots and pans and stick to their frocks and gossip and leave men’s work to the men.” At first read, I thought this was simply the sexism of the 1950’s on full display in a book from that very different era. But the more I read the more I realised it wasn’t just that. Fleming writes Bond intentionally as a sexist misogynistic dinosaur and explores this aspect of his character more than any other.

Bond is ice, and over the course of the job Vesper slowly melts him. I was expecting Bond to be as charming as Sean Connery but there’s very little charisma or warmth to the character for most of the novel. He’s cold and mean and grumpy. Not an exuberant spy with one arm ‘round a woman and the other ‘round the neck of an enemy. He feels more like a pencil pusher on a business trip. This Bond is a thinker rather than a man of action, going through all possible contingencies in his head before making any move, almost like Sherlock Holmes. And Bond must do his best thinking in the shower because he takes an awful lot of them for such a short novel. Every other passage begins with “After a cold shower…” His car – a supercharged Bentley – is his only personal hobby. Bond’s a machine for his government who achieves self-awareness and begins to question his programming after a near-death experience.

Bond is ice, and over the course of the job Vesper slowly melts him. I was expecting Bond to be as charming as Sean Connery but there’s very little charisma or warmth to the character for most of the novel. He’s cold and mean and grumpy. Not an exuberant spy with one arm ‘round a woman and the other ‘round the neck of an enemy. He feels more like a pencil pusher on a business trip. This Bond is a thinker rather than a man of action, going through all possible contingencies in his head before making any move, almost like Sherlock Holmes. And Bond must do his best thinking in the shower because he takes an awful lot of them for such a short novel. Every other passage begins with “After a cold shower…” His car – a supercharged Bentley – is his only personal hobby. Bond’s a machine for his government who achieves self-awareness and begins to question his programming after a near-death experience.

In the book’s final third, Bond becomes a surprisingly deep character and he begins to debate the nature of evil with Mathis. An entire chapter in the pithy novel is dedicated to the discussion, composed primarily of a monologue from a freshly-reawakened Bond, literally and metaphorically. Post-war, how can one differentiate the good guys from the bad? He questions his government and their motives – their meddling – in a way that feels fiercely modern. I was shocked by its inclusion considering the lack of depth of the early adaptations of the books on the big screen. These are the questions Daniel Craig’s Bond struggles with and I had no idea they came from the original books and not the institutional distrust that arose post-9/11 when his incarnation of the character began.

While Bond is presented as colder and uncompassionate when compared to most screen adaptations, he’s also more human and vulnerable too. Early in Casino Royale, he barely survives an assassination attempt by sheer luck (and incompetent would-be assassins) and is left shaken by the experience. He feels like he’s going to vomit and later, after a horrific torture session I’ll discuss in a moment, he cries tears of self-pity. In fact, all of the classic ‘spy stuff’ and action happens around Bond and he’s an unwilling participant. Mathis is the one who combs for listening devices and deals with them when they’re discovered, and the Frenchman is the one to interrogate suspects and gain information. Bond doesn’t kill anyone, or even fire his weapon. His only actions are to throw himself backwards off a chair to knock over a hidden gunman, and then later he tries to kick the same man but the villain dodges and captures Bond. That’s the extent of it.

While Bond is presented as colder and uncompassionate when compared to most screen adaptations, he’s also more human and vulnerable too. Early in Casino Royale, he barely survives an assassination attempt by sheer luck (and incompetent would-be assassins) and is left shaken by the experience. He feels like he’s going to vomit and later, after a horrific torture session I’ll discuss in a moment, he cries tears of self-pity. In fact, all of the classic ‘spy stuff’ and action happens around Bond and he’s an unwilling participant. Mathis is the one who combs for listening devices and deals with them when they’re discovered, and the Frenchman is the one to interrogate suspects and gain information. Bond doesn’t kill anyone, or even fire his weapon. His only actions are to throw himself backwards off a chair to knock over a hidden gunman, and then later he tries to kick the same man but the villain dodges and captures Bond. That’s the extent of it.

The card game at the centre of Casino Royale is treated as the big action set piece. One where each turn of the card, narrowing of the eyes, and bead of sweat plays like a western duel. It is quite a remarkable sequence considering I had no idea what was going on most of the time. Unlike the film adaptation in which Bond and Le Chiffre play poker, the game is baccarat. While Fleming’s written descriptions meant I could tell a good hand from a bad, the exact details of the game were lost on me. The chapter dedicated to Bond explaining the rules went right over my head. They might as well have been playing Go Johnny Go Go Go Go. I find watching gambling scenes to be far more enjoyable than reading about them because in that medium the direction, editing, acting, and music can all make the narrative beats and twists easier to understand, even if you don’t know the rules. However, those baccarat chapters are worth reading simply for all the many wonderful similes Fleming has to come up with to describe the green table the cards slide across.

With a little help from the CIA monetary fund, Bond beats Le Chiffre but soon finds the stakes have been raised. Vesper is kidnapped and Bond races off to save her only to be captured himself. Bond is stripped naked and given a literal bollocking with a carpet beater; a torture scene that’ll make you cross your legs despite the restraint when it comes to the gory details. Le Chiffre is an interesting villain because he’s not the classic world-dominator who wants to murder millions and torture Bond simply for the sadistic thrill of it. He’s a pathetic, failing man who made some bad investments in French brothels and porno theatres and has now become cruel out of sheer desperation. Other than his vocation and reliance on an inhaler, little of Mads Mikkelsen’s version of the character matches the novel’s, with Fleming at one point hilariously describing his physicality as being “with the silence and economy of movement of a big fish.”

Bond survives long enough for Le Chiffre’s embarrassed employers, SMERSH, to enter and kill the villain, saving Bond in the process. SMERSH means “death to spies” and is said to be responsible for the death of Trotsky in an attempt by Fleming to meld his fictional world of spycraft with real events. While Bond’s near-death experience is a key factor in what occurs in the final chapters of the book, it is a little disappointing for Bond to only be abstractly responsible for Le Chiffre’s death rather than pulling the trigger himself. With Le Chiffre dead and Bond recuperating, the story seems finished but a third of the book remains, and its with this final act that Fleming sets his sights on the aforementioned depth of Bond, detailing his thoughts on his job and his growing love for Vesper. Up until this point Bond is apathetic about Vesper other than the possibility of sleeping with her. When she’s kidnapped, he doesn’t much care about saving her. If she dies in the process that’s too bad. At least, that’s what he’s trying to convince himself.

Bond survives long enough for Le Chiffre’s embarrassed employers, SMERSH, to enter and kill the villain, saving Bond in the process. SMERSH means “death to spies” and is said to be responsible for the death of Trotsky in an attempt by Fleming to meld his fictional world of spycraft with real events. While Bond’s near-death experience is a key factor in what occurs in the final chapters of the book, it is a little disappointing for Bond to only be abstractly responsible for Le Chiffre’s death rather than pulling the trigger himself. With Le Chiffre dead and Bond recuperating, the story seems finished but a third of the book remains, and its with this final act that Fleming sets his sights on the aforementioned depth of Bond, detailing his thoughts on his job and his growing love for Vesper. Up until this point Bond is apathetic about Vesper other than the possibility of sleeping with her. When she’s kidnapped, he doesn’t much care about saving her. If she dies in the process that’s too bad. At least, that’s what he’s trying to convince himself.

“This is not a romantic adventure story in which the villain is finally routed and the hero is given a medal and marries the girl. Unfortunately, these things don’t happen in real life.” Despite Bond initially recognising this, he falls in love with Vesper against his better judgement. The final pages play out like a romantic travelogue; a holiday with the couple as they sunbathe and, of course, treat themselves to the finest food. The entire relationship is described from Bond’s point-of-view and more often than not Vesper is written as a mysterious object of desire rather than a fully-realised character. This is however somewhat vital given the soon-to-be-revealed twist about Vesper’s true motive. There is genuine love and affection between them but they initially consummate this and sleep together almost like a contract being signed. It’s like she owes him one and his torture was her fault so she needs to make it up to him. It’s also mentioned that Bond is just desperate to put his recently-battered penis to the test and fears impotence. Plus, her secretive nature would mean sleeping with her would “have the sweet tang of rape”. Oh, the 1950’s!

I’ve been debating with myself about whether Bond has an actual arc on his perception of women or whether his original position is confirmed by Casino Royale’s final chapter. Just when he decides to marry her, Vesper kills herself due to her guilt at being a double agent for the Russians and because those Russians are coming to the hotel to kill her, and likely Bond in the process. It’s played like an almost heroic sacrifice but Bond only sees betrayal. “Bitch” is the first and last thing he calls her in the book, the devastating final line being, “The bitch is dead now”. There was love there. Bond had changed his view on women and his extreme sexism muted. But now he returns to his old mindset and claims to be even more steadfast in those opinions. He realises he has to think the way he did before Vesper entered his life to survive in this line of work. After all his philosophising about love and evil, the enemy is now clear again after Vesper’s death: SMERSH.

I’ve been debating with myself about whether Bond has an actual arc on his perception of women or whether his original position is confirmed by Casino Royale’s final chapter. Just when he decides to marry her, Vesper kills herself due to her guilt at being a double agent for the Russians and because those Russians are coming to the hotel to kill her, and likely Bond in the process. It’s played like an almost heroic sacrifice but Bond only sees betrayal. “Bitch” is the first and last thing he calls her in the book, the devastating final line being, “The bitch is dead now”. There was love there. Bond had changed his view on women and his extreme sexism muted. But now he returns to his old mindset and claims to be even more steadfast in those opinions. He realises he has to think the way he did before Vesper entered his life to survive in this line of work. After all his philosophising about love and evil, the enemy is now clear again after Vesper’s death: SMERSH.

It’s left ambiguous just how much of this humanity that Vesper brought forth in Bond remains and to what degree he’s gone back to his programming. As Casino Royale concludes, he claims and acts like he’s the cold, uncompromising agent again, but he’s lied to himself about Vesper and her influence on him before and I think he’s doing it again. Somewhere, deep down, some warmth remains. As an avid fan of the films, I was surprised how much of a serious character study Casino Royale is. I do like a balance between the more serious aspects of the character and the silly bombast of, say, the Roger Moore era films, but I really did enjoy the small-scale intimacy of the debut Bond novel. It’s also remarkable how close the 2006 film adaptation is to the book, at least when the action moves to the casino and Vesper enters the story, considering the 53-year and 24-film separation. The narrative may be shockingly small-scale considering the franchise it would spawn, but Casino Royale remains a strong introduction to Fleming’s original vision of James Bond.

Stay tuned to OutofLives for my thoughts on the second of Fleming’s Bond novels, Live and Let Die, in the coming weeks.