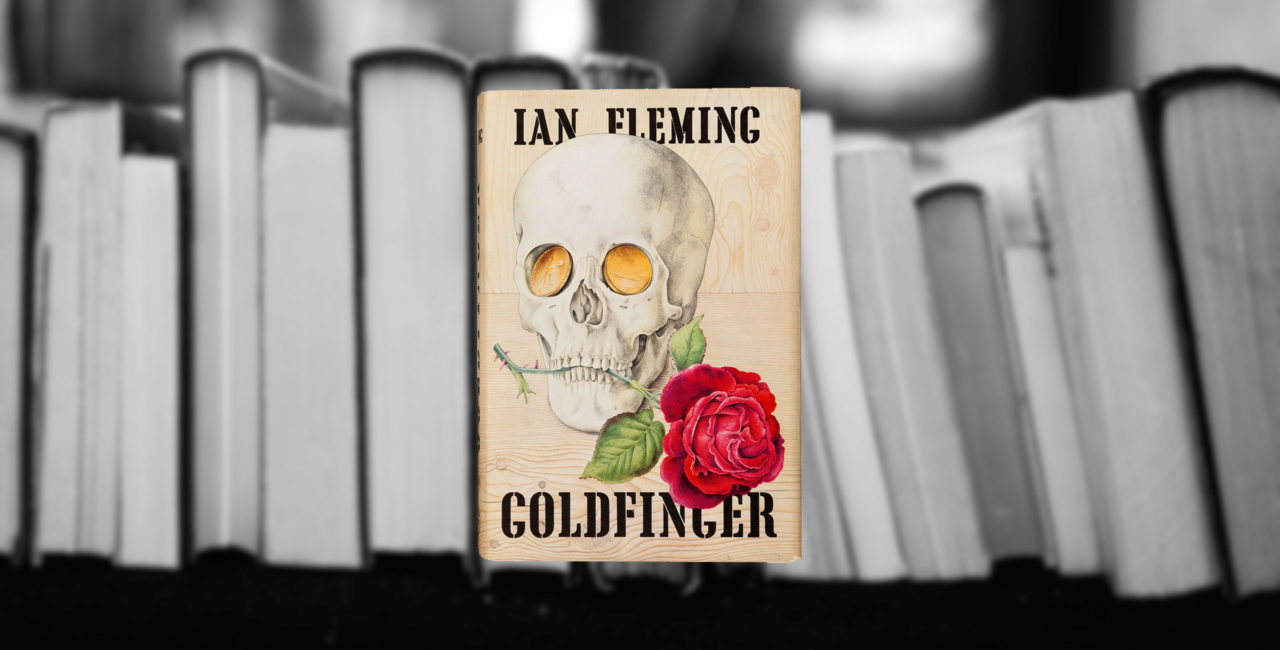

Goldfinger marks a concerted effort by Ian Fleming to humanise his literary spy, James Bond. Despite what some say about the early novels, 007 has always been more than a blunt weapon, but seven books in, Fleming is having to further develop the character to prevent the series from going stale. The novel opens with Bond at Miami airport, reflecting on a job that went bad, leading him to have to kill a Mexican with his bare hands. He tries to justify his actions by thinking of all the death that happens in the world but can’t quite manage it, his victim’s eyes burned into his mind. In the previous two novels Bond has been desperate for a new mission, a chance to prove himself, but now he’s tired. He wants the soft life he once detested, and it becomes clear this bipolar response to his addictive work dominates his life. A simple chapter of Bond drowning his sorrows in an airport lounge is one of the most insightful of the series.

A delayed plane gives Bond the perfect excuse to take the night off, get drunk, and forget. However, a chance encounter changes his new plans. Mr Junius Du Pont reintroduces himself to Bond and the reader is placed in Bond’s shoes: “where do I know that name from?” It turns out the rich American was sat next to Bond at Casino Royale for his card game with Le Chiffre. Du Pont is having trouble losing at cards, the game being Canasta, and enlists Bond’s aid in proving his rival, Mr Goldfinger, a cheat. That’s right, there’s no hiding it, Fleming is officially out of ideas and is using the exact same set-up as Moonraker. An off-the-books personal mission for a friend to identify how one of the world’s richest men, now Goldfinger instead of Drax, is cheating and why. This begins the novel’s penchant for lazy repetitiveness and unbelievable coincidences that slowly drag the story down.

A delayed plane gives Bond the perfect excuse to take the night off, get drunk, and forget. However, a chance encounter changes his new plans. Mr Junius Du Pont reintroduces himself to Bond and the reader is placed in Bond’s shoes: “where do I know that name from?” It turns out the rich American was sat next to Bond at Casino Royale for his card game with Le Chiffre. Du Pont is having trouble losing at cards, the game being Canasta, and enlists Bond’s aid in proving his rival, Mr Goldfinger, a cheat. That’s right, there’s no hiding it, Fleming is officially out of ideas and is using the exact same set-up as Moonraker. An off-the-books personal mission for a friend to identify how one of the world’s richest men, now Goldfinger instead of Drax, is cheating and why. This begins the novel’s penchant for lazy repetitiveness and unbelievable coincidences that slowly drag the story down.

After living with the film adaptation ever since I was an unquestioning child, it only struck me how silly a character Auric Goldfinger actually is when I began reading about him. Because AU is the periodic symbol for gold, his name is essentially Golden Goldfinger, the man obsessed with gold. It may be ludicrous but I appreciate the simplicity: he wants not nebulous power or political gain, only gold. Well, this is the case until its not. It’s later revealed that he is the treasurer for SMERSH and therefore does have a political affiliation, which I feel ruins the character somewhat. The Daniel Craig films have suffered from an unnecessary linking of villains so it’s interesting to see that this issue plagued Fleming too. Goldfinger’s SMERSH connections makes him seem like a cross between Mr Big and Drax rather than his own independent tyrant, and From Russia with Love felt like a conclusion to the SMERSH storyline.

Goldfinger made his fortune running pawn shops, which isn’t the most glamourous villain origin, although he became one of the world’s richest men and began illegally smuggling his wealth overseas. The pawn business, and the fact that at one point he has to leave to personally bail one of his workers out of jail, makes Goldfinger seem a bit small fry for Bond and more like a self-obsessed contestant from The Apprentice, at least for the novel’s first two-thirds. Yet interestingly, polar opposite to the mysterious Dr No, Goldfinger dominates the novel and features prominently from beginning to end. He’s certainly engaging to the reader because Bond becomes obsessed with the man, his white – or gold – whale, and, of course, he looks weird too. “It was as if Goldfinger had been put together with bits of other people’s bodies.” Namely the five-foot body of Danny DeVito and the perfectly round head of Karl Pilkington.

Goldfinger made his fortune running pawn shops, which isn’t the most glamourous villain origin, although he became one of the world’s richest men and began illegally smuggling his wealth overseas. The pawn business, and the fact that at one point he has to leave to personally bail one of his workers out of jail, makes Goldfinger seem a bit small fry for Bond and more like a self-obsessed contestant from The Apprentice, at least for the novel’s first two-thirds. Yet interestingly, polar opposite to the mysterious Dr No, Goldfinger dominates the novel and features prominently from beginning to end. He’s certainly engaging to the reader because Bond becomes obsessed with the man, his white – or gold – whale, and, of course, he looks weird too. “It was as if Goldfinger had been put together with bits of other people’s bodies.” Namely the five-foot body of Danny DeVito and the perfectly round head of Karl Pilkington.

Much like the film, Bond identifies how Goldfinger is cheating: his assistant spying his rival’s cards with a pair of binoculars from a hotel window. Despite being so similar in plot to Moonraker, what breathes new life into the sequence is Bond’s attitude and persona. He’s actually having fun. Bond takes great pleasure in the act of screwing over Goldfinger, finding it a sweet distraction for an hour or two. He mocks Goldfinger through his earpiece and flirts with his assistant Jill Masterton, oblivious to how dangerous the situation will become. Bond’s euphoria carries over to the reader and it’s enjoyable to read such a different side to the character who is usually so serious when on a mission. This is immediately contrasted when the novel jumps forward in time and Bond is depressed again, on night duty in the office writing his own unarmed combat handbook, titled ‘Stay Alive’, and refusing to drink tea because it led to the downfall of the British Empire. It’s almost as if Fleming occasionally forgets he’s writing fiction and turns Goldfinger autobiographical.

Bond sits thinking of Goldfinger, the man of incredible wealth who cheats at card games. The man is his personal obsession rather than his directed mission. Well, until M calls Bond into his office and makes it his mission. Bond laughs when M mentions Goldfinger, coincidence and chance continuing to be powerful forces in the novel, and I can’t tell whether it is for a thematic reason or just for plotting convenience. While it’s done far too often in the new films, I quite like the idea of Fleming’s Bond taking on a mission for himself without MI6 but no, M tells him to investigate the man he has already been investigating just so the novel can adhere to the classic formula. I feel it’s such a missed opportunity and perfectly fits Bond’s headspace to take on such a personal vendetta.

Bond sits thinking of Goldfinger, the man of incredible wealth who cheats at card games. The man is his personal obsession rather than his directed mission. Well, until M calls Bond into his office and makes it his mission. Bond laughs when M mentions Goldfinger, coincidence and chance continuing to be powerful forces in the novel, and I can’t tell whether it is for a thematic reason or just for plotting convenience. While it’s done far too often in the new films, I quite like the idea of Fleming’s Bond taking on a mission for himself without MI6 but no, M tells him to investigate the man he has already been investigating just so the novel can adhere to the classic formula. I feel it’s such a missed opportunity and perfectly fits Bond’s headspace to take on such a personal vendetta.

For years I had heard that in the novels Bond drives a Bentley rather than the Aston Martins seen prominently in the films so it was a great surprise to read differently. Bond drives a battleship grey Aston Martin DB III in Goldfinger, although the gadgets only consist of a reinforced bumper and fancy lights, but still, it’s an enjoyable addition. He travels to Kent for a game of golf with Goldfinger and, again, the similarities with previous books become an issue. The golf club is just ten miles away from Drax’s base from Moonraker. If Fleming is going to ape his own work and repeat characters and plots then the least he could have done is mix up the locations. It’s just like the Jamaican island headquarters of both Mr Big and Dr No being so close together. Fleming writes what he knows and sadly he only knows one Caribbean Island and a small patch of England. I hope there is more variety in the globetrotting in the back half of the novel series because so far it has been a disappointing element.

What isn’t disappointing however is the golf game itself which is easily the best I’ve ever read. Although, thinking about it, it’s probably the only one I’ve ever read. It’s such a tense sequence, beating any of the actual action scenes of the series. Fleming commits to writing all 18 holes in detail, never skipping forward, and it doesn’t feel repetitive. The lead is traded between the two men throughout the game, Bond being the more unpredictable golfer and Goldfinger having almost mechanical consistency. As something of a golfer myself, I much preferred it to any of the card games.

What isn’t disappointing however is the golf game itself which is easily the best I’ve ever read. Although, thinking about it, it’s probably the only one I’ve ever read. It’s such a tense sequence, beating any of the actual action scenes of the series. Fleming commits to writing all 18 holes in detail, never skipping forward, and it doesn’t feel repetitive. The lead is traded between the two men throughout the game, Bond being the more unpredictable golfer and Goldfinger having almost mechanical consistency. As something of a golfer myself, I much preferred it to any of the card games.

Bond has to act as someone other than himself, someone potentially employable to Goldfinger, and while he hated doing this in Diamonds Are Forever, he now loves it, continuing this idea of Bond becoming a lighter character. Goldfinger cheats but Bond bests him with a final cheat himself, again much like Drax, and it’s an incredibly satisfying moment. I did find it interesting that the two men play with Dunlop and Penfold balls unlike the film, which I imagine must have been changed just because it’s more fun hearing Connery attempt to say “Slazenger”.

After the game of golf, Bond is introduced to Oddjob, Goldfinger’s Korean manservant/bodyguard. At this point Fleming has almost made it 150 pages without being hideously racist – a personal best – but Oddjob becomes an outlet for some of the most atrocious statements yet that I’m not going to repeat here. I’ll only mention that at one-point Goldfinger throws Oddjob his naughty pet cat and tells him to eat it for his dinner, which is in no way intended as a joke. Goldfinger himself is hardly physically threatening so Oddjob serves his narrative purpose as ‘the muscle’ well, certainly being a most dangerous adversary for Bond. He’s an adept martial artist (which Bond, the man writing a book on unarmed combat, dismisses as “weird combat stuff”) and has bizarre crusty hands and feet with no nails that are super strong, able to smash through mantelpieces easily. He’s hardy much of an actual character but as an example of a Bond trope Oddjob is one of the best.

At this point it becomes clear just how much of an improvement the film adaptation of Goldfinger is over the novel. Everything is tightened up: the pacing is radically improved, motives are clearer, and characters enter and exit at more appropriate times. When people ask the question of whether there is a film actually better than the book, I have a new answer: Goldfinger. After the golf there is no other narrative drive than ‘What’s Goldfinger up to?’ and while there are great moments and set pieces, the book drags. Bond drives across Europe following Goldfinger and Fleming writes the journey with the same intense detail as the golf game but, sadly, with none of the tension. By the time he finally reached Switzerland I was bored out of my mind. There was more humanising though, with Bond finding himself hungry after forgetting to buy lunch.

At this point it becomes clear just how much of an improvement the film adaptation of Goldfinger is over the novel. Everything is tightened up: the pacing is radically improved, motives are clearer, and characters enter and exit at more appropriate times. When people ask the question of whether there is a film actually better than the book, I have a new answer: Goldfinger. After the golf there is no other narrative drive than ‘What’s Goldfinger up to?’ and while there are great moments and set pieces, the book drags. Bond drives across Europe following Goldfinger and Fleming writes the journey with the same intense detail as the golf game but, sadly, with none of the tension. By the time he finally reached Switzerland I was bored out of my mind. There was more humanising though, with Bond finding himself hungry after forgetting to buy lunch.

While Bond is tailing Goldfinger he bumps, or rather crashes, into Tilly Masterton, who is also chasing the megalomaniac. The two instantly have chemistry, or as Fleming puts it, “Their eyes met and exchanged a flurry of masculine/feminine master/slave signals.” I wish there was more of Tilly in the book, although she certainly hangs around longer than her film counterpart. She’s a capable and driven young woman on her own mission, which would have made for a good parallel with Bond if he too were on a personal vendetta. Tilly’s presence also unlocks the next element of Bond’s humanity: humour. After their cars collide, Bond looks at the damage and says “If you touch me there again, you’ll have to marry me.” Tilly does the correct thing and follows up his smarmy comment with a slap to the face.

Bond is lighter and quippier than before with some truly terrible jokes. Everyone talks about how Fleming’s Bond is so serious but the people who say this have clearly never read past the first couple of books. Seven novels in, he becomes the man who straightens his tie after he kills someone. This is the Bond of the films; witty and bemused, even when in danger. There were moments of this Bond in earlier novels but it came to the fore in Dr No and is now unleashed entirely. Dr No was Fleming understanding the silliness he was writing and Goldfinger is when Bond himself starts to recognise and react to the absurdity. I wonder that if the first films had been based on the early books whether Bond as a cinematic character would have been different. I imagine he’d have been more serious from the very start with much less humour, but I’m glad they began with these middle novels.

Bond is lighter and quippier than before with some truly terrible jokes. Everyone talks about how Fleming’s Bond is so serious but the people who say this have clearly never read past the first couple of books. Seven novels in, he becomes the man who straightens his tie after he kills someone. This is the Bond of the films; witty and bemused, even when in danger. There were moments of this Bond in earlier novels but it came to the fore in Dr No and is now unleashed entirely. Dr No was Fleming understanding the silliness he was writing and Goldfinger is when Bond himself starts to recognise and react to the absurdity. I wonder that if the first films had been based on the early books whether Bond as a cinematic character would have been different. I imagine he’d have been more serious from the very start with much less humour, but I’m glad they began with these middle novels.

Tilly wants revenge for her sister’s death at the hands of Goldfinger, who painted her gold, suffocating the skin. This is an iconic detail of the film but in the book it’s only mentioned in passing, retold afterwards rather than experienced by Bond – another improvement by the film. I do like the added detail however that Goldfinger routinely hypnotises prostitutes and paints them gold in an attempt to make love to the precious metal. An argument between Bond and Tilly gets them caught and Goldfinger straps Bond to a table with a saw slowly moving between his legs. It’s not the memorable laser from the film but, while it’s less original, I think I like the saw more. It’s certainly more visceral and imaginable. Unlike the film, Goldfinger does want Bond to talk and when he doesn’t, he knocks him unconscious.

What follows is a strange chapter where Bond thinks he’s dead, drifting in-and-out of consciousness, and imagining he’s traveling up to heaven. This could be insightful but all he thinks about is how awkward it would be for all his girlfriends to meet each other, particularly Vesper. But he’s quickly brought back down to Earth, New York to be specific, and Goldfinger details his plan to steal 15 billion dollars worth of gold from Fort Knox with the help of some gangsters, taking the golden heart of America with him when he emigrates to Russia. To do so he needs to poison a whole town with a nerve toxin and even use an atomic bomb. Suddenly Goldfinger poses much more of a threat. Bond underestimated him, as did I. And what’s Bond and Tilly’s roles in all this? Why, they are to be Goldfinger’s secretaries, of course. I kept expecting a twist on why they were allowed to live, a secret plan to use them somehow by Goldfinger, but no, he just needs his paperwork filing. It’s an incredibly weak piece of plotting.

What follows is a strange chapter where Bond thinks he’s dead, drifting in-and-out of consciousness, and imagining he’s traveling up to heaven. This could be insightful but all he thinks about is how awkward it would be for all his girlfriends to meet each other, particularly Vesper. But he’s quickly brought back down to Earth, New York to be specific, and Goldfinger details his plan to steal 15 billion dollars worth of gold from Fort Knox with the help of some gangsters, taking the golden heart of America with him when he emigrates to Russia. To do so he needs to poison a whole town with a nerve toxin and even use an atomic bomb. Suddenly Goldfinger poses much more of a threat. Bond underestimated him, as did I. And what’s Bond and Tilly’s roles in all this? Why, they are to be Goldfinger’s secretaries, of course. I kept expecting a twist on why they were allowed to live, a secret plan to use them somehow by Goldfinger, but no, he just needs his paperwork filing. It’s an incredibly weak piece of plotting.

One gangster involved in Goldfinger’s plot is Pussy Galore, a failed trapeze artist turned cat burglar who runs the exclusively lesbian gang ‘The Cement Mixers’. Galore is an iconic piece of the Bond canon but the character herself pales in comparison to her legacy and preposterous name. She’s a huge disappointment. Much of this comes from the fact that there are now two ‘Bond girls’ in the story at the same time when there only really needed to be one. Fleming fleshes out neither but keeps both around. I can now see why Tilly was killed off early in the film adaptation to make way for Pussy. Galore also barely interacts with Bond; a meaningful glance there, a brush of the shoulder here. She’s introduced late, doesn’t do anything, and doesn’t talk to Bond. What a romance!

The other terrible, terrible aspect of Pussy Galore is the treatment of her sexuality. So far Fleming has painted homosexuality as a villainous, disgusting trait and now decides to be homophobic from a new angle. Bond, with Fleming’s voice barely disguised behind him, says that gay people are “a direct consequence of giving votes to women and ‘sex equality’. As a result of fifty years of emancipation, feminine qualities were dying out or being transferred to the males. Pansies of both sexes were everywhere.” Bond sees lesbians as nothing but a challenge for men, a challenge he conquers by the end of the novel when he magically ‘cures’ Pussy with his intoxicating manliness. It’s very much an attitude from the time the books were written but even away from the offensiveness it adds nothing to the story. Unlike Gala Brand’s dismissal of Bond’s charm in Moonraker, Pussy’s lesbianism – and later Tilly’s, who falls for Pussy herself – reveals nothing of Bond’s character other than repugnant attitudes.

The other terrible, terrible aspect of Pussy Galore is the treatment of her sexuality. So far Fleming has painted homosexuality as a villainous, disgusting trait and now decides to be homophobic from a new angle. Bond, with Fleming’s voice barely disguised behind him, says that gay people are “a direct consequence of giving votes to women and ‘sex equality’. As a result of fifty years of emancipation, feminine qualities were dying out or being transferred to the males. Pansies of both sexes were everywhere.” Bond sees lesbians as nothing but a challenge for men, a challenge he conquers by the end of the novel when he magically ‘cures’ Pussy with his intoxicating manliness. It’s very much an attitude from the time the books were written but even away from the offensiveness it adds nothing to the story. Unlike Gala Brand’s dismissal of Bond’s charm in Moonraker, Pussy’s lesbianism – and later Tilly’s, who falls for Pussy herself – reveals nothing of Bond’s character other than repugnant attitudes.

Bond manages to send a message to his pal Felix Leiter, revealing Goldfinger’s plan, but, as the crew journeys to Fort Knox to enact the plan, he doesn’t know if it has been received or not. It makes for an exciting finale and my brain couldn’t keep up with my darting eyes on the page, desperate to know what happens. It’s also impossible to read this section without John Barry’s score to Operation Grand Slam running in one’s mind. Yet disappointment follows. The heist never really gets underway before Felix and the army interrupt the proceedings. Bond and Goldfinger never get near Fort Knox and instead remain on the train as it is raided. Suddenly Bond escapes, has a fist fight with Oddjob that the book has been building up to yet lasts only two seconds, and then the baddies escape as Bond randomly fires a bazooka at the train. It’s such a rushed conclusion. Tilly dies in the brief battle after deciding to run to Pussy instead of stay with Bond, with Fleming all but outright stating that it was her lesbianism that killed her. Just awful.

Yet this wouldn’t be a Bond story without a villain’s reprise. Bond is kidnapped on his way out of the country by Goldfinger, Oddjob, and Pussy. Again wasted, Oddjob doesn’t put his fighting skills to good use and is instead sucked out of a plane window, but Goldfinger’s death is more impactful. “For the first time in his life, Bond went berserk.” Fleming humanises Bond in a final, brutal way when he drops the suave persona and lets emotion take him, strangling Goldfinger to death. A glossed-over emergency landing later and Bond and Pussy are in bed together, the gangster having switched sides and helped Bond escape. “They told me you only liked women”, says Bond. “I never met a man before”, replies Pussy. But before it ends Fleming gives Pussy’s backstory, including her being raped by her uncle at the age of 12. I actually thought he was going to make it through a whole novel without using rape as key part of a female character’s backstory but there it was on the very last page.

Yet this wouldn’t be a Bond story without a villain’s reprise. Bond is kidnapped on his way out of the country by Goldfinger, Oddjob, and Pussy. Again wasted, Oddjob doesn’t put his fighting skills to good use and is instead sucked out of a plane window, but Goldfinger’s death is more impactful. “For the first time in his life, Bond went berserk.” Fleming humanises Bond in a final, brutal way when he drops the suave persona and lets emotion take him, strangling Goldfinger to death. A glossed-over emergency landing later and Bond and Pussy are in bed together, the gangster having switched sides and helped Bond escape. “They told me you only liked women”, says Bond. “I never met a man before”, replies Pussy. But before it ends Fleming gives Pussy’s backstory, including her being raped by her uncle at the age of 12. I actually thought he was going to make it through a whole novel without using rape as key part of a female character’s backstory but there it was on the very last page.

Overall, Goldfinger is a mixed bag of a Bond novel. Primarily it made me appreciate the film even more. I already thought it a classic but now I see it as one of the most improved upon book-to-film adaptations. The eponymous villain himself is a great character and adversary for Bond, and dominates the book like no other villain before him. It’s his story as much as 007’s. You can really feel the effort from Fleming to develop Bond into a more human character in several ways, from making him more emotional, jokey, and contemplative. That’s the novel’s biggest success. However, while there are great set pieces and moments, the connective tissue between them is flawed and often dull. The finale is rushed and the Bond girls probably the weakest yet. But the most memorable part of the book is by far its wonderful golfing sequence. Despite all the criticisms of the book I have, that tense round of golf is my favourite piece of Fleming’s writing so far.

Stay tuned to OutofLives for my thoughts on the eighth of Fleming’s Bond books, his first short story collection, For Your Eyes Only, in the coming weeks.

As us espionage illuminati know too well, Ian Fleming isn’t around to write another “Trout Memo” or choose the next 007! He has not only eulogised and promoted the “espionage industry” but he has also spread so much disinformation about that industry that even MI6 would have been proud of the dissemination of so much fake news. Maybe the Bond legacy is finally coming to an end notwithstanding the recent publication of Anthony Horowitz’s With a Mind to Kill, particularly after Daniel Craig’s au revoir in No Time To Die.

We think the anti-Bond era is now being firmly established in literature and on the screen. Raw noir anti-Bond espionage masterpieces are on the ascent. Len Deighton’s classic The Ipcress File has been rejuvenated by John Hodge with Joe Cole aspiring to take on Michael Caine and of course there are plenty of Slow Horses ridden by Bad Actors too.

Then there’s Edward Burlington in The Burlington Files series by Bill Fairclough, a real spy (MI6 codename JJ) who disavowed Ian Fleming for his epic disservice to the espionage fraternity. After all, Fleming single-handedly transformed MI6 into a mythical quasi-religious cult that spawned a knight in shining armour numbered 007 who could regularly save the planet from spinning out of orbit.

Last but not least, the final nail in wee Jimmy Bond’s coffin has been hammered in by Jackson Lamb. Mick Herron’s anti-Bond sentiments combine lethally with the sardonic humour of the Slough House series to unreservedly mock not just Bond but also British Intelligence which has lived too long off the overly ripe fruits Fleming left to rot! Time for a fresh start based on a real spy so best read Beyond Enkription in The Burlington Files series by ex-spook Bill Fairclough.

Do look up the authors or books mentioned on Amazon, Google The Burlington Files or visit https://theburlingtonfiles.org and https://everipedia.org/wiki/lang_en/bill-fairclough and read Beyond Enkription.