The eighth book in the original Ian Fleming run of James Bond adventures differs from the previous seven. Instead of being a novel, For Your Eyes Only is a collection of five short stories, and a curious one at that. While, at first, I was unsure of the format, ultimately I found that the book offers enlightening details on Bond and may even act as the best introduction to Fleming’s enduring character.

From a View to a Kill

From a View to a Kill is the Bond series at its most perfunctory and procedural, a perfectly adequate adventure that offers little of substance. The story begins with Bond in Paris and plays like another of Fleming’s travel guides. We’re given the rundown on where he stays and what he eats and drinks while visiting in the city, an Americano being the least offensive of the musical comedy drinks found in French cafés. These descriptions pad out a few pages and offer little of interest for modern readers, however there are some character insights as it progresses. Bond despises the city, claiming he can see shame in the eyes of its occupants since the war. We learn he lost his virginity to a prostitute in the city at age 16 and often fantasises about meeting a French girl before reminding himself of their terrible skin and garlic breath.

Breaking Bond from his daydreams, and the reader from their cringing, comes Mary Ann Russell, Number 765 of the Service, stationed in France. She drives Bond to his latest assignment in a battered Peugeot she had to buy to get away from the Frenchmen on the train who pinch her arse black and blue. In this respect Russell feels like a step up from the usual female characters of the series and Fleming has become more self-aware of his treatment of them. She’s patronised by the men but capable, even calling them out on their nonsense: “You’re just a lot of children playing at Red Indians.” Every element of the story has to be rushed and condensed to fit the short story format, meaning she falls in love with Bond instantaneously, but even despite that I find her to be one of the better Fleming Bond girls.

Breaking Bond from his daydreams, and the reader from their cringing, comes Mary Ann Russell, Number 765 of the Service, stationed in France. She drives Bond to his latest assignment in a battered Peugeot she had to buy to get away from the Frenchmen on the train who pinch her arse black and blue. In this respect Russell feels like a step up from the usual female characters of the series and Fleming has become more self-aware of his treatment of them. She’s patronised by the men but capable, even calling them out on their nonsense: “You’re just a lot of children playing at Red Indians.” Every element of the story has to be rushed and condensed to fit the short story format, meaning she falls in love with Bond instantaneously, but even despite that I find her to be one of the better Fleming Bond girls.

It turns out that a motorbike courier working for SHAPE NATO was intercepted and Bond is tasked to figure out why and how. M and Bond are obsessed with proving that independent British Intelligence can do what NATO, with the “top security brains of fourteen countries”, can’t. Proving this point feels like the sole reason for the entire story and at times it reads like a Brexit manifesto. But when there is action it’s very well written. The story opens with the death of the courier and Fleming can make a single person being shot just as thrilling as a large-scale action set piece.

In a very Sherlock Holmes twist, Bond has to spy the invisible man, find the killer posing as someone no one else notices, and it turns out to be a caravan of Gypsies in the area who dug out a little underground base and left a three-man crew of implied Russians to run operations from it. Despite knowing where the base is, Bond poses as a bike courier unnecessarily to act as bait, but it’s a fun scene. In the final confrontation, Mary proves her worth and actually saves Bond, a great atypical twist to a fairly dull tale.

From a View to a Kill is an enjoyable, quick read but by far the least interesting of the collection. The needed brevity forces out some aspects, such as a developed villain, here replaced by faceless goons, but the story does focus on some specific spycraft elements, which, along with Mary, are the story’s strengths.

For Your Eyes Only

The collection’s title story begins with a brilliant scene reminiscent of the opening of Inglorious Basterds. Major Gonzales, a smiling villain who charms and threatens simultaneously, pays an unwelcome visit to Colonel Havelock and his wife’s Jamaica home and states his intention to purchase their land. When they refuse, he mercilessly guns them down. This begins a key theme that runs throughout the story: the times they are a-changin’. There are suddenly new owners of a plantation owned by the same family for 300 years. Bond misses the sound of old lawnmowers when they are replaced by new ones. He prefers old planes rather than the new, faster, higher ones. Even Hammerstein, the big bad and Gonzales’ boss, is a Nazi fleeing persecution: the last of an old enemy making way for the new. It’s a story of revenge and the pain of that which is gone forever.

The collection’s title story begins with a brilliant scene reminiscent of the opening of Inglorious Basterds. Major Gonzales, a smiling villain who charms and threatens simultaneously, pays an unwelcome visit to Colonel Havelock and his wife’s Jamaica home and states his intention to purchase their land. When they refuse, he mercilessly guns them down. This begins a key theme that runs throughout the story: the times they are a-changin’. There are suddenly new owners of a plantation owned by the same family for 300 years. Bond misses the sound of old lawnmowers when they are replaced by new ones. He prefers old planes rather than the new, faster, higher ones. Even Hammerstein, the big bad and Gonzales’ boss, is a Nazi fleeing persecution: the last of an old enemy making way for the new. It’s a story of revenge and the pain of that which is gone forever.

The Havelocks are friends of M and we catch up with him struggling with what action to take. Is pursuing the killer revenge or justice, and is it an appropriate use of the Service? Seeing the strong, fatherly figure of these novels in a vulnerable position is powerful and, in a rather cowardly action, he pushes the decision onto Bond and has him decide. Bond, the tool, the weapon, is now the decision maker and vows revenge on behalf of M. This is such a great set-up for a Bond story. It’s not Bond on the personal vendetta as we’ve seen countless times now in the films but M, who has to use Bond. I would love to see this idea in a future film. It maintains the personal stakes the new movies are obsessed with but transposes them to M.

For Your Eyes Only is the most Bond has ever felt like an assassin. He’s given a target, a gun, and a location. He sees himself as the public executioner for an ignorant society. Pest control. I love seeing the human side of Bond but reading about him suppressing that and treating the mission in a cold, methodological manner is truly chilling. “Never send a man where you can send a bullet”, Fleming writes. Bond travels to Canada for the ‘execution-type deal’ and I was so excited that finally we were getting a new country to add to Fleming’s travelogue. I didn’t have to hear him talk about the USA, Jamaica, or France again. And while that’s true, he doesn’t really write about Canada very much either. For once he has nothing to say, or more likely nothing to complain about.

While staking out Hammerstein’s home and garden, in which the villain walks around with his knob constantly hanging out, like a Nazi John Barrowman, Bond encounters Judy Havelock, the daughter of the murdered Havelocks. Judy has also vowed revenge and plans on eliminating the baddies with a bow, and it all feels very much like a repeat of the sequence in Goldfinger with Tilly Masterson. I do like Judy and her headstrong attitude of wanting to do it her way, which Bond responds to with “Don’t be a silly bitch. This is man’s work”, but in a story of restricted length, her appearance, combined with the repetitive beats of books past, does feel somewhat unnecessary and only included because it’s part of the formula.

While staking out Hammerstein’s home and garden, in which the villain walks around with his knob constantly hanging out, like a Nazi John Barrowman, Bond encounters Judy Havelock, the daughter of the murdered Havelocks. Judy has also vowed revenge and plans on eliminating the baddies with a bow, and it all feels very much like a repeat of the sequence in Goldfinger with Tilly Masterson. I do like Judy and her headstrong attitude of wanting to do it her way, which Bond responds to with “Don’t be a silly bitch. This is man’s work”, but in a story of restricted length, her appearance, combined with the repetitive beats of books past, does feel somewhat unnecessary and only included because it’s part of the formula.

After a brilliantly slow and tense build-up, all hell breaks loose and Hammerstein and Gonzales are killed by Bond and Judy. They are satisfying deaths, despite being from afar, but there is a tinge of disappointment at the end considering how much I enjoyed the bulk of the story. Judy suddenly becomes subservient, apologies to Bond, and then kisses him. For a story about revenge, when it is finally fulfilled Fleming has little to say about it. It’s just the end of the story and the thematic work that was so strong lacks a final statement. Despite the final fumble however, I would have gladly read a full novel of For Your Eyes Only, and overall it is one of my favourite James Bond stories.

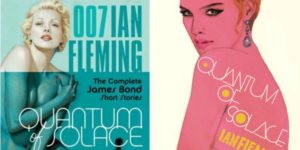

Quantum of Solace

“This story may seem to you on the dull side. But would you care to hear it?” Quantum of Solace is the most unique Bond story from Fleming, dispensing with the formula to try and reveal new aspects of the character. Bond is at a dinner party with the governor of Nassau and his millionaire friends and hating it. He’s out of his comfort zone, having to make banal small talk and discuss vapid gossip. When the others leave, Bond and the governor are left alone in awkwardness, neither wants to converse but it is expected of them. I love seeing Bond so uncomfortable in a relatable situation. We hear of the ease at which he recently dealt with a job sabotaging Cuban rebels, but small talk? He’s terrified, and begins to lie and say outrageous things just to amuse himself. To fill the time the governor decides to tell Bond a story.

“This story may seem to you on the dull side. But would you care to hear it?” Quantum of Solace is the most unique Bond story from Fleming, dispensing with the formula to try and reveal new aspects of the character. Bond is at a dinner party with the governor of Nassau and his millionaire friends and hating it. He’s out of his comfort zone, having to make banal small talk and discuss vapid gossip. When the others leave, Bond and the governor are left alone in awkwardness, neither wants to converse but it is expected of them. I love seeing Bond so uncomfortable in a relatable situation. We hear of the ease at which he recently dealt with a job sabotaging Cuban rebels, but small talk? He’s terrified, and begins to lie and say outrageous things just to amuse himself. To fill the time the governor decides to tell Bond a story.

It is the story of Philip Masters, a socially awkward and sexually inexperienced operative for the Service in Nigeria. On a plane he falls in love with an air hostess, Rhoda Llewellyn, in what is perhaps the most romantic encounter Fleming has ever written. The electricity in the air, her stray hair touching his cheek, a secret smile, a brief gaze. There’s none of the series’ usual thuggery towards sex, and it’s interesting that it is contained to a story within a story. Can such romance only be fiction, at least in Bond’s eyes? Soon darkness enters the tale however. Rhoda marries Philip thinking his life is exciting yet it’s anything but. The marriage becomes strained; she has an affair with her golfing partner and Philip attempts suicide.

Rhoda vows to stand by Philip but he refuses, unable to forgive her. A secret divorce is arranged and the two pretend to be married for image’s sake. In private they don’t talk and their home is split in two, each having to stay in their selected rooms. When Philip finally leaves, he offers Rhoda his car but this is not the gift it at first seems but rather revenge. Payments on the car have not been made, leaving her further in debt. The story ends with ruthless heartbreak. But there’s a twist, as if the governor lives in a house marked ‘Number 9’. Rhoda was actually at the dinner party earlier that evening, a Mrs Harvey Miller, sat next to Bond having remarried. During dinner he thought her a bore and the story is supposed to teach Bond a lesson: not to judge those around him without knowing their story. He’s not the only one with an interesting life.

This story of Philip and Rhoda is somewhat trite but that’s the point. It may not be the most exciting of Fleming’s writing but it is incredibly insightful. Bond comments that “suddenly the violent dramatics of his own life seemed very hollow.” Bond, a spy who has saved the world on multiple occasions, is obsessed with a soap opera narrative. As the story progresses, he gets more and more invested, desperate to know what happens. Domestic life is alien to Bond and therefore excites him for he is denied it. He’s very much the inverse of most people, especially the reader who was hoping for an action thriller. Despite the depravity of the story-within-a-story, it’s Bond who we end up feeling sorry for.

This story of Philip and Rhoda is somewhat trite but that’s the point. It may not be the most exciting of Fleming’s writing but it is incredibly insightful. Bond comments that “suddenly the violent dramatics of his own life seemed very hollow.” Bond, a spy who has saved the world on multiple occasions, is obsessed with a soap opera narrative. As the story progresses, he gets more and more invested, desperate to know what happens. Domestic life is alien to Bond and therefore excites him for he is denied it. He’s very much the inverse of most people, especially the reader who was hoping for an action thriller. Despite the depravity of the story-within-a-story, it’s Bond who we end up feeling sorry for.

“Incurable disease, blindness, disaster – all these can be overcome. But never the death of common humanity in one of the partners. I call it the Law of the Quantum of Solace.” The governor’s philosophy on relationships gives the short story its rather silly title, it referring to the one piece of decency that stops a relationship failing even at its most perilous moments. If you can’t offer a quantum of solace to your partner, a bestial cruelty will awaken. The story as a whole is surprisingly pretentious coming from pulpy paperback Fleming but that makes it all the more fascinating. I don’t know if the short story is wholly successful but I like Fleming being experimental with the format rather than just condensing a regular Bond tale down to 40 pages.

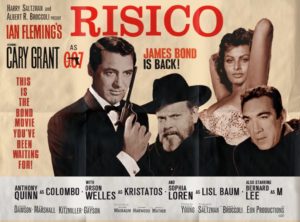

Risico

M doesn’t employ men with beards. Upon hearing this idiosyncrasy, I began wishing that one of the short stories in this collection would centre around M rather than Bond. As the books have progressed, we’ve been finding out more and more about Bond’s superior and father figure, and while he’s a character I’ve always liked, I’m gaining new appreciation for him. He’s described as similar to Churchill and now that’s exactly how I picture him; it’s such a perfect comparison I can’t believe I hadn’t seen it before. M hates sending his men after drug smugglers, seeing it as a misuse of the Service, although it wouldn’t surprise me if, like Churchill, he enjoys the occasional snort himself. Yet he sends Bond to the Mediterranean anyway to get information from Kristatos, a double agent willing to reveal the identity of drug barons, who says “In this pizniss is much risico.”

M doesn’t employ men with beards. Upon hearing this idiosyncrasy, I began wishing that one of the short stories in this collection would centre around M rather than Bond. As the books have progressed, we’ve been finding out more and more about Bond’s superior and father figure, and while he’s a character I’ve always liked, I’m gaining new appreciation for him. He’s described as similar to Churchill and now that’s exactly how I picture him; it’s such a perfect comparison I can’t believe I hadn’t seen it before. M hates sending his men after drug smugglers, seeing it as a misuse of the Service, although it wouldn’t surprise me if, like Churchill, he enjoys the occasional snort himself. Yet he sends Bond to the Mediterranean anyway to get information from Kristatos, a double agent willing to reveal the identity of drug barons, who says “In this pizniss is much risico.”

Kristatos puts Bond on the trail of ‘The Dove’ Enrico Columbo, the most successful smuggler in the Mediterranean and the spitting image of Toad of Toad Hall. I knew I was enjoying the story when Fleming managed to make me like one of the most annoying villain tropes going: eating. I hate when baddies are chomping on an apple or even sitting down for a three-course dinner while questioning the hero. I get it, it’s a power move, but it’s annoying and overdone, yet Risico is different. Columbo eats because he’s anxious, munching in a clumsy and angry way. In a short time, the supporting characters of the story become some of the most engaging in the entire Bond canon.

Columbo’s Viennese lover, Lisl Baum, tricks Bond into meeting her and sets a trap. This is a story in which Bond is manipulated at every turn, the subject of espionage usually he would employ. It’s great to see Bond constantly on the back foot having entered a world he doesn’t understand. He feels more like an old Noir detective in Risico rather than a secret agent. It’s a shame though that we never get his thoughts on his multiple failures. The sequence of Bond realising he has been led into a trap and fleeing, leading to a chase on the beach, is superb. Bond being outnumbered, cornered, and captured is seen often in the films but is something new for Fleming.

The story also features some great old-school spycraft. Bond identifies Kristatos from the drink he has on his table and there’s a fantastic scene of Columbo listening in to their conversation via a recorder hidden in a chair, which is subtly moved around the restaurant in a ballet under Bond’s nose. Bond’s cover is that he’s a writer of adventure stories and looking to get into the film industry. This is no doubt a meta joke on Fleming’s part but one that works, and I like Bond actually putting at least some effort into having a cover identity. It does him little good however when he’s captured and taken to Columbo where the truth is revealed. Kristatos pointed Bond to an innocent competitor and is in fact the drug runner himself! Bond is duped again but he joins forces with Columbo to take down Kristatos’ operation.

The story also features some great old-school spycraft. Bond identifies Kristatos from the drink he has on his table and there’s a fantastic scene of Columbo listening in to their conversation via a recorder hidden in a chair, which is subtly moved around the restaurant in a ballet under Bond’s nose. Bond’s cover is that he’s a writer of adventure stories and looking to get into the film industry. This is no doubt a meta joke on Fleming’s part but one that works, and I like Bond actually putting at least some effort into having a cover identity. It does him little good however when he’s captured and taken to Columbo where the truth is revealed. Kristatos pointed Bond to an innocent competitor and is in fact the drug runner himself! Bond is duped again but he joins forces with Columbo to take down Kristatos’ operation.

Risico culminates in one of the biggest action sequences of the entire series – a firefight between forces on the docks, the scale being that of one of the Bond films. It’s been fun to see the scale of action increase as the books continue; Bond didn’t fire his gun in Casino Royale and now he’s taking on a small army. Using some Tobias Funke-esque cat-like agility, Bond is able to reach Kristatos and kill him, and Columbo offers him Lisl as a reward, she apparently having no say in the matter. Overall, I thought Risico was brilliant. A twisty action adventure where Bond is the right combination of fallible and heroic, and the story distills the essence of Bond into a quick 50 pages.

The Hildebrand Rarity

The Hildebrand Rarity finds Bond in the Seychelles, relaxing post-mission, and hunting a stingray purely because it looks evil. Either that or he’s still upset about Steve Irwin’s death. Along with his friend Fidele Barbey, he joins the crew of a yacht owned by Milton Krest in order to catch the rare fish that gives the short story its title. And so begins another unique Bond tale very unlike those found in the novels. There’s no mission or prior knowledge of anyone involved on Bond’s part, the holidaying agent instead finds himself in the midst of an impromptu Hitchcockian mystery.

The Hildebrand Rarity finds Bond in the Seychelles, relaxing post-mission, and hunting a stingray purely because it looks evil. Either that or he’s still upset about Steve Irwin’s death. Along with his friend Fidele Barbey, he joins the crew of a yacht owned by Milton Krest in order to catch the rare fish that gives the short story its title. And so begins another unique Bond tale very unlike those found in the novels. There’s no mission or prior knowledge of anyone involved on Bond’s part, the holidaying agent instead finds himself in the midst of an impromptu Hitchcockian mystery.

Fleming does a wonderful job of making Milton Krest totally despicable without straying into the usual arch megalomaniacal characteristics of his villains. Krest doesn’t want world domination, he’s just a dick. An arrogant dick with a villainous amount of shag pile carpet. He speaks a lot and disguises insults as jokes, giving people nicknames in an attempt to rile them up. He’s unlikable in a very realistic way. Bond guesses Krest’s “forced maleness” is a result of impotency, and describes him as a “a grand slam redoubled in bastards.” Krest is also a tax evader who thinks he can buy anything and siphons everything through his charitable organisation, which seems a little rich considering the James Bond franchise will come to house several tax exiles. Fleming himself targeting the super-rich from his home in Jamaica doesn’t quite feel right.

The Hildebrand Rarity features James Bond at his most conflicted about committing murder. Yet it’s the murder of fish rather than people he’s struggling with. Once the rare fish is discovered, Bond’s nature as a precise assassin is to grab the lone fish, whereas Krest deems it easier to poison the water and kill thousands to get to the one he wants. We see the limits of Bond’s unemotive killer nature and he begins to feel compassion, using the fish as a proxy for life in general. He evens starts calling the fish “people”. Bond is a much more vulnerable character than usual throughout the story, insulted by Krest and upset about fish murder. He eventually sabotages the poison drop to spite Krest in a moment where he’s at his most petty and relatable. Yet the fish is found and killed nonetheless, leaving Bond heartbroken.

While travelling on the Yacht, Milton Krest is shown to abuse his wife Elizabeth, whipping her with the tail of a stingray which he calls “The Corrector.” Again, this angers Bond, who must be an open palm kinda guy. It is intriguing to see Bond, the sexist womaniser, suddenly want to protect women, but this continues the idea of Bond being a much softer character when not on an assignment. One night, Krest is murdered using the rare fish and it’s left ambiguous who committed the crime. Bond himself finds the body and covers it up to look accidental. I say it’s ‘ambiguous’ but Elizabeth clearly has the clearer motive. I wish there was more reason for it to be someone else in order to tighten the mystery, the only other suspect is Fidele, who Krest openly insulted.

While travelling on the Yacht, Milton Krest is shown to abuse his wife Elizabeth, whipping her with the tail of a stingray which he calls “The Corrector.” Again, this angers Bond, who must be an open palm kinda guy. It is intriguing to see Bond, the sexist womaniser, suddenly want to protect women, but this continues the idea of Bond being a much softer character when not on an assignment. One night, Krest is murdered using the rare fish and it’s left ambiguous who committed the crime. Bond himself finds the body and covers it up to look accidental. I say it’s ‘ambiguous’ but Elizabeth clearly has the clearer motive. I wish there was more reason for it to be someone else in order to tighten the mystery, the only other suspect is Fidele, who Krest openly insulted.

The mystery of the killer is never solved but Bond is, again, shaken by the experience. He goes from hoping Elizabeth would kill her husband to disturbed when it (most likely) happens, the sheer coldness of her vengeance shocks him. In many ways The Hildebrand Rarity feels like a companion piece to Quantum of Solace in which we see the governor’s law in action first hand. The short stories allow us to witness Bond in positions not found during his formulaic core novels and, once again, he is disturbed by the harshness of domestic life.

Conclusion.

Having From a View to a Kill as the first short story in the collection gets the book off to a bad start. The reader is liable to think the stories are nothing but fairly empty, uninteresting, condensed missions that offer little new insight into James Bond and the world he inhabits. But the following four stories prove that not to be the case. For Your Eyes Only, in totality, is one of the best James Bond books I’ve read so far. The stories offer an intriguing mix of genre-bending narratives and revelations surrounding new facets of Bond’s humanity, whether suppressed while on a revenge mission or laid bare in more domestic situations. Bond is still cool and charming but more fallible and vulnerable, and therefore more interesting, than ever before. Casino Royale should still be the first port of call for new James Bond readers but if you want actual insight and depth to Bond as a character, look no further than For Your Eyes Only.

Stay tuned to OutofLives for my thoughts on the ninth of Fleming’s Bond novels, Thunderball, in the coming weeks.