The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Sanditon. Weir of Hermiston. The great unfinished novels offer a certain mystique and allure; a sense of curiosity; the tease of an insight into a literary process begun but never completed. The Man with the Golden Gun is not one of these works. Ian Fleming, tired and suffering from illness, wasn’t happy with his final James Bond novel and died before he could return to the manuscript to fix it. What was published, posthumously, was just a rough first draft as devoid of life as its author. The Man with the Golden Gun is easily one of the worst novels in Fleming’s canon, despite the occasional flash of inspiration.

Fleming wrote the novel with the film series having just begun, taking the cinematic world by storm more than he took the literary. It’s hard not to think of the possible influence of the films while reading The Man with the Golden Gun, particularly its opening. Are the first few chapters Fleming’s attempt at a pre-title scene? James Bond returns to London but not as we know him. After suffering from amnesia and searching for his identity in the Soviet Union, Bond is taken into the charge of Colonel Boris of the Leningrad Institute and brainwashed. His new, subconscious mission is to kill M. This is a great idea for a Bond story, one I’m surprised the films have never attempted, but it feels somewhat wasted here, used as a cold open twist rather than be actually explored as a concept.

“James Bond frowned. He didn’t know that he had frowned and he wouldn’t have been able to explain why he had done so.” The novel’s protagonist, our hero, is now a most unsettling man. We are no longer privy to his thoughts, likely because they are not his own, and the debonair Bond is now almost an automaton, going through the motions of entering his place of work to reach M. This is some of Fleming’s best work in the novel, making Bond a nefarious presence, referring to him by his full name of “James Bond” throughout. He sits in an upright posture, holding a newspaper but never reading it, and when he is told to wait ten minutes, he waits for exactly ten minutes. Humanity instead comes pouring from unlikely sources, like the usually dry Bill Tanner, to offset this new James Bond.

James Bond is a weapon; he says as such. First for M and the British government and then for the KGB, a tool sent back to kill its master. Bond’s identity as a killer, a gun himself whom others pull the trigger, is a key theme of the novel. Well, at least at the beginning and the end; we’ll get to the incredibly vacuous and dull middle in due time. M, or Sir Miles Messervy as we find out, narrowly avoids death by pressing a hidden button that drops a glass screen in front of his desk, saving him from the squirting poison gun Bond fires at him. How does he respond? Why, by having his former agent subdued and sent to be un-brainwashed, of course. Simple. Instead of any repercussions, M plans to fix Bond’s brain and send him back out on an assignment. But is Bond being un-brainwashed (Fleming actually uses this word) or just brainwashed again?

M knows that Bond is right, he is a tool. A firing piece, and he knows just where to point him. To fix Bond, M will send him after Scaramanga and he’ll either return as a hero or die in the field, a win either way. Bond needing to be corrected somehow by a mission more dangerous than any before is growing to be a tired concept, You Only Live Twice began in a similar way. This is where the quality of the novel steeply declines. Everything is just so rushed. By page 40, Bond has tried to kill M, has been successfully counter-conditioned, received his new mission, and is six weeks into tracking Scaramanga across the Caribbean. He was heading for Cuba but then discovers Scaramanga is actually in Jamaica, which is a huge disappointment. Fleming teased us with a new location for a Bond story and then snatched it away, instead setting yet another novel in his beloved Jamaica.

As enjoyable as the opening of The Man with the Golden Gun is, Fleming wants the reader to forget all about it. Once given his mission, Bond is just back to being Bond, stuck in an airport as always. You would think this would have been a harrowing experience for Bond but his only thoughts on the matter are a laughably generic, “one must forget the bad and remember the good.” He moves on with his life with just the briefest of mentions of his six weeks of treatment and 24 ECT sessions that magically returned him to normal. “The results had been miraculous.” I’m not expecting a modern exploration into PTSD or anything but there are no consequences whatsoever. What was even the point of doing this to Bond? It feels like Fleming had the idea for the opening, which couldn’t fill more than a few chapters, and so just glued it onto the start of what becomes a standard Bond adventure. The best part of the novel suddenly becomes meaningless.

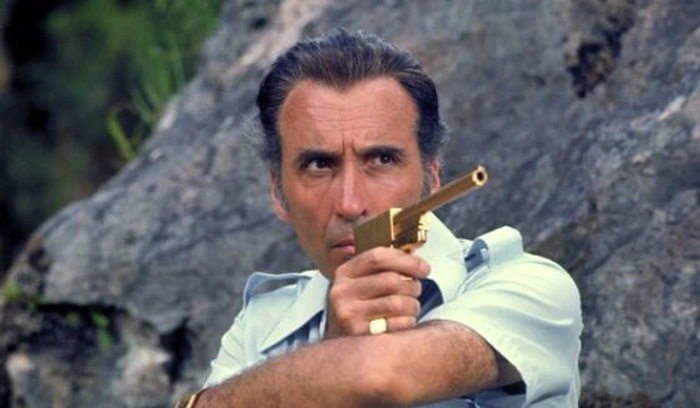

One way to have Bond’s brainwashing vital to the rest of the novel would be to have him go after the KGB, a revenge plot with Bond pinging back and forth as a weapon between both sides. But no, Bond instead is sent after Francisco Scaramanga, a freelance assassin known for his golden gun. Scaramanga is a local legend in the Caribbean, almost a celebrity, and is essentially a wild west gunman, having worked for the Spangled Mob in Las Vegas for a while. While the Spangled Mob has given us some of the worst antagonists of the novels, I do like that Fleming is maintaining a continuity and manages to weave new characters into his existing interconnected world. I never expected the novels to be so linked. Of course, Scaramanga also has a physical abnormality, a third nipple, which is an extraneous detail that just feels like Fleming ticking what has become a cliché off of the list.

As a teenager, Scaramanga, a circus performer, watched his elephant gunned down by police and in return killed them, putting him on a path of death and apathy. It’s an odd backstory but gets the job done, and is fairly emotional. But the most fascinating aspect of Scaramanga is the psychology Fleming imbues on him. MI6 files state that Scaramanga sees the gun as an extension of his penis and that brandishing it is a form of sexual fetishism. I’ve always enjoyed the disturbing scene in the film that implies this, where he caresses his lover with the barrel of his gun, so I’m glad it is further explored in the book when it couldn’t in the film – outside of the lyrics of the title song, of course.

Scaramanga is also possibly gay because he can’t whistle, which is an odd bit of logic that would be uncomfortable to read about if it wasn’t so funny an idea, and M even tests to make sure he can whistle and is relieved when he can. There’s also reference to the power and excitement of guns, the psychological appeal of them, the ability they grant to extend your will and reach in the world. Scaramanga demands power after feeling powerless, which is a fascinating idea but it never extends beyond the pages of the MI6 file which introduces him.

While in Jamaica, Bond meets with his former secretary Mary Goodnight who has taken on a new Secret Service posting on the island. The two kiss upon their first meeting, and the professional relationship they have had over the last couple of books suddenly becomes personal. This is a new tact for Fleming, building up a relationship over multiple books, but it’s not very successful. It doesn’t feel like growth or a transition but rather an abrupt change. Goodnight is prudish and strait-laced, embarrasses easily, doesn’t smoke, rarely drinks, and is very excitable about the intricacies of her work. Yet her characterisation matters little because she’s barely in the book. Her inclusion feels more like an afterthought really. Every book needs a Bond girl and she’s there to tick that particular box. In fact, she fills two roles as both the love interest and the local ally giving Bond information on his surroundings. I miss when the Bond girls were more integral to the plots of the books.

Scaramanga enters the story like a Western gunslinger, almost shifting the novel’s genre. He comes down from the top floor of a brothel, which might as well be a saloon, gun on his hip, looking to start a fight with the proprietor and Bond. To prove his skill, he quick draws and shoots two pet birds and then tries to get Bond to smell his smoking pistol. This is where we get some great, overripe, pulpy dialogue: “Thanks. I’ve tried it. I recommend the Berlin vintage. 1945. But I expect you were too young to be at that tasting.” I do enjoy Bond and Scaramanga’s first interactions, with the two men trying to size each other up, and at the end you don’t know whether they are going to shoot each other or hug. There is some bad dialogue as well though, “stop trying to lean on me. I’m unleanable-on,” and Scaramanga is another in the long line of American gangsters Fleming writes like a cartoon character. His irritating catchphrase is “got the photo?” instead of ‘got the picture?’

Scaramanga, based on this chance encounter, hires Bond to be his bodyguard/assistant while he has a business meeting/party with fellow criminal shareholders in a hotel he is building. It’s disappointing that the most dangerous hitman in the world isn’t in a story about his deadly profession but instead one that concerns business deals and admin, creating a tax haven that I’m sure most of the filmmakers behind the early Bond films would have loved to cash in on. The gangsters talk while Bond is essentially the PA, which is exactly what happened already in Goldfinger, and this is the beginning of every story thread and location in The Man with the Golden Gun feeling like a less interesting re-tread of what has come before.

The hotel is such a boring location and the 100 pages stuck there, half of the novel, are lifeless and tiresome. It also feels far too similar to The Spy Who Loved Me. If you’re searching for themes or plot developments, they can be found at the beginning and end of the novel; the middle feels totally empty. The half-built hotel is barely described, just blank walls and empty rooms, despite it being on a stunning Caribbean Island. It might as well be the Linton Travel Tavern. Maybe the exoticism, as well as the thematic statements and character insights, would have been added in a second draft. This part of the novel feels like nothing but a basic framework of the plot. Bond has the opportunity to kill Scaramanga but he refuses to in cold blood. This should be because of his recent experience with M but no, that correlation is never made. Instead, Bond starts needling Scaramanga, pricking his vanity until an honest fight breaks out. But in the meantime, Bond just takes showers endlessly and hangs around. Oh, and Felix Leiter makes a surprise appearance, also being undercover on the island. You know, like Thunderball.

After redefining the modern criminal organisation with SPECTRE in books past, Ian Fleming unveils his new bad guy supergroup in The Man with the Golden Gun: “The Group.” It’s a group of gangsters so generic that Kevin McClory’s claim that he was the creator of SPECTRE and that Fleming stole the idea suddenly begins to sound completely truthful. Made up of American mob bosses and a man called Hendriks who represents the KGB, Scaramanga presides over the meeting of The Group, although there is talk of a mysterious employer, Mr C. I wish it was evil Cooper from Twin Peaks but it’s implied to be Castro, which is a fascinating development to see Fleming name a real person as the next big bad Bond villain after Blofeld. The Group burn sugar fields to inflate prices, smuggle drugs, and commit industrial sabotage. Bond learns these things that we have no reason to care about by listening through a door with a glass to his ear. That is the extent of his actions for most of the book, although even that is useless because Felix has bugged the room anyway. Bond might as well not be there.

“Stupidly, he wanted to assert his personality over this bunch of tough guys who rated him insignificant.” With Bond and Scaramanga in a deadlock, both knowing the other is their enemy but unable to act on it just yet, the duel takes on the form of showboating across a strange few chapters. Bond has to put on a party for the visiting gangsters and it reminded me far too much of that episode of The IT Crowd, ‘Jen the Fredo’. Bond shoots a woman’s hat off, without permission, and then demands she strip naked and dance. Then a nude, oiled woman comes out and starts grinding on a giant leather hand. Bond describes it as an orgy, he himself aroused. It’s a barmy part of the book where James Bond basically becomes a pimp. Scaramanga, the character the book is named after and the first villain in a while to appear for a considerable amount of time in a novel, does little but watch. Thankfully, finally, with the page count running out, he begins to plot Bond’s death and Bond realises it: “It was as if he were a bit of steak and they were wondering whether to have it done rare or medium rare.”

Further adding to the western theme, The Group and Bond visit a mock-up American train station and travel on the locomotive. Again, this is exactly the same as what happened in a previous book, Diamonds Are Forever. A dummy made to look like Goodnight is tied to the tracks and, finally, there’s a satisfying crash of violence, including Bond putting a bullet between Hendriks’ eyes. In the action, Bond compares guns with Scaramanga and the examination is clearly metaphor for potency, with Bond trying to prove he’s still got it after the failure of his last mission. The train erupts in chaotic gunfire and although Bond is in the centre of it, he can barely see what is going on. I am fairly disappointed in Scaramanga’s skill as a gunman here. Instead of being deadly accurate, he just starts wildly shooting everywhere with a very Frank Reynolds mindset of “so anyway, I started blasting.”

Both Scaramanga and Bond are shot, the latter resigned to his own death. “Ah, well! He’d take as many of them as he could with him.” This is hardly the examination of death that dominated You Only Live Twice and the nonchalant attitude on the subject doesn’t sit right with me, not after his growth in the previous novel. But fear not, Felix Leiter is here. The American comes to the rescue, saving Bond and driving the train off a cliff killing everyone except himself, Bond, and Scaramanga, who jump to safety. Felix has the gangsters disarmed and ready to arrest but he brutally murders them instead and yet there’s no comment on this. The entire book has seen Bond refusing to kill in cold blood and yet he has no opinion to share when Felix does it. Of course, Felix is horribly injured in the action, a leg twisting at an unnatural angle, but he survives once again, truly cementing his place as the Kenny/Dr. Chilton of the James Bond series.

Like two beasts in the scrub, Bond and Scaramanga come face-to-face, both bleeding and near death in the harsh sun. Bond struggles to kill the injured Scaramanga, standing over him for minutes, holding the gun. This is where the themes present at the start of the book, Bond as a weapon, return. I love this chapter. Scaramanga claims they are both killers, both equally guilty, and the comparisons between the characters that should have been present throughout are finally made. Scaramanga attacks again, forcing Bond’s hand, and they shoot each other, Scaramanga dead and Bond hit with a poisoned bullet, similar to what Bond used against M at the start of the book. I like the drama of the scene, and it is a well-written final confrontation in a lacklustre book, but would this have worked better in an earlier novel as a way to get to know Bond? Contemplating his role as a weapon feels like something that would affect Bond more early in his career. 13 books in, after all the killing, I don’t know if I buy Bond only just feeling like this now.

While recovering in hospital, Felix offers his thoughts on Bond’s conundrum: “It’s what you were put into the world for. Pest control.” This is the final word on the matter and Bond seems to take it to heart, which is a disappointing point to leave the argument on. While recovering, Bond receives the Jamaican Police Medal but declines a knighthood; M’s approval is enough, which is a nice touch. Besides that, The Man with the Golden Gun has a very generic, standard ending. Bond is left recovering in Jamaica with the cliché ‘prize’ at the end of his mission being the girl, Mary Goodnight. “He knew, deep down, that love from Mary Goodnight, or from any other woman, was not enough for him.” This line struck me as strange because it feels like Tracy never existed and that that genuine love has been forgotten simply for the ease of having new love interests. Anyway, the true romance is between Bond and Felix who are obsessed with each other in this book. It’s a lame ending, especially compared to the brilliant ones of the last two books.

After the SPECTRE trilogy, which could have easily and fittingly been the end of the James Bond series, Fleming used The Man with the Golden Gun as a new beginning. A brand-new adventure to launch the character into new anthological stories like the early books, but the new beginning sadly became the end when Fleming died, making The Man with the Golden Gun an extraneous oddity. It has a strong opening that takes Bond into new territory but then retreats into the formula of old, re-treading scenes, actions, and locations from books past. Fleming seemed to be out of ideas. There are themes touched on that could make for a fascinating novel but they aren’t properly explored, with the middle of the book being a true low point of the series with interminable pacing, a lacklustre villain, and the most forgettable Bond girl. I don’t like being too harsh on The Man with the Golden Gun given the circumstances under which it was written, a dying man making an admirable attempt at completing one last novel, but it is a disappointing read. Although, thankfully, it is not quite the end: one last compilation of short stories remains.

Stay tuned to OutofLives for my thoughts on Fleming’s final Bond book, Octopussy and The Living Daylights, in the coming weeks.