Ian Fleming’s first short story collection, For Your Eyes Only, is a perfect introduction to the character of James Bond, perhaps more so than his novel debut Casino Royale. The format offers a greater variety of stories and potentially more potent characterisation than the novels, if properly taken advantage of. Yet Fleming’s second collection is not an introduction but a farewell, the final published piece of the canon because of his untimely death. Is Octopussy and The Living Daylights a worthy conclusion to the creator’s take on the legendary character? Let’s take it story-by-story…

Octopussy.

Octopussy is an odd fish. Jamaica is yet again the setting, something that would irritate me if there wasn’t actual purpose behind the choice this time. The story focuses on a Major Dexter Smythe who is without a doubt a stand-in for Fleming. Yet Smythe’s role as an author surrogate doesn’t make him a ‘Mary Sue’, quite far from it, because there’s a fascinating level of self-hatred to be found in the work. Smythe is a retired military man in Jamaica who spends his time swimming on his private beach, just like Fleming, and is a man in ill health with heart issues yet refuses to stop smoking and drinking, again like Fleming. He’s a lonely man with a death wish and one wonders where the similarities end, if indeed they do, with Fleming’s own death imminent. Smythe’s “general disgust with himself had eroded his hard core into dust” yet he finds solace in fish, who he sees as people, none more so than his octopus named Octopussy, who he has been plucking up the courage to feed by hand.

This is where Bond enters the story, and it’s a very different Bond than we’re used to. He’s not the protagonist and instead is simply more of a catalyst for the story to begin. I like the idea of Bond stories focusing on other people, where a single encounter with the man changes the course of their lives. Just another afternoon for him is the defining moment in someone else’s existence, like The Spy Who Loved Me but, you know, good. Without having access to Bond’s thoughts, the character is portrayed as serious and mysterious; the cold official in the suit. Smythe describes him as “The Bond Man” and it’s great to read that, after so many stories, Bond can still be this enigmatic figure to the reader as well as the characters. This is very much Bond as a policeman rather than a spy as he visits Smythe seeking justice for a dark secret from his past. The story reminded me very much of J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls, with Bond in the Inspector Goole role, turning up on the doorstep and exposing a guilty conscience.

The majority of the story is told through flashback where Smythe, working in a very similar unit to Fleming did during the Second World War, discovers the location of some hidden Nazi gold and kidnaps a mountaineer named Hannes Oberhauser to help him reach the mountainside stash. The characterisation here is great with Smythe slowly going from the protagonist I just assumed I was supposed to root for to a wholly unlikable man as we learn his plot. As silly as it sounds, even the way he eats sausages, tearing them and getting bits caught in his teeth, stuck in my head and reveal him to be an animalistic predator. Conversely, Oberhauser grows more likable and sweet, making his swift and brutal death all the more upsetting. The flaw however is that most of the recollection is less about the morality of Smythe’s actions and more about the logistics of them. It begins to read as a manual for how to get heavy gold bars down a mountain.

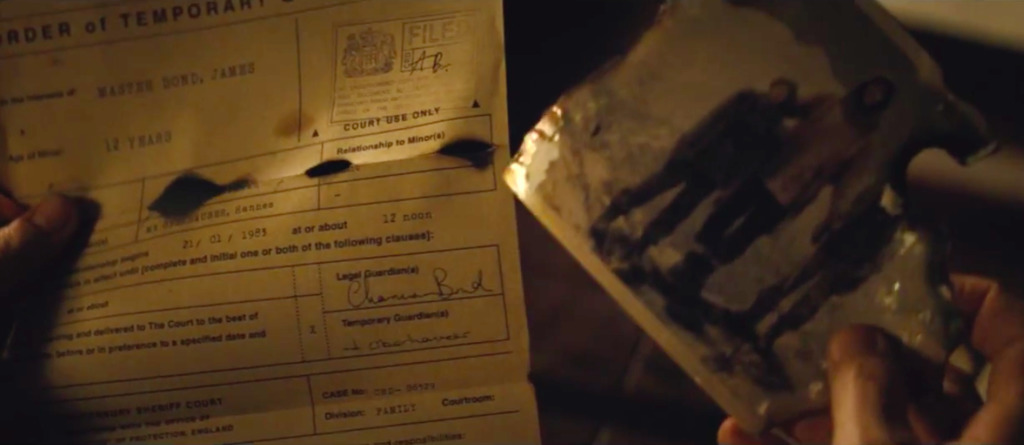

Content with Smythe’s confession, Bond reveals Oberhauser’s body has been found and that the man was a father to him for a year in the Alps during his youth, teaching him to ski. Bond leaves Smythe a week before police come to arrest him, allowing him the opportunity to kill himself to keep the case quiet, but also with a hint of vengeance from Bond. In some ways, Octopussy plays like a greatest hits of Fleming’s short stories: the personal revenge of For Your Eyes Only, the fish obsession of The Hildebrand Rarity, and even the domestic drama of Quantum of Solace when we learn of Smythe’s wife Mary who has killed herself. While Smythe contemplates taking the same action, he ultimately decides to go to court and get rich off the publicity – his final repugnant action – but not before he visits Octopussy one last time.

Overall, I enjoy Octopussy, there are plenty of interesting angles to the story, including the mystery of why Fleming’s final Bond villain is a surrogate for himself (one for the psychologists), but it does feel as shallow as the waters Smythe swims in. Take the final few pages, for example: Smythe is poisoned by a fish and when he visits his beloved Octopussy before his imminent, accidental death the octopus eats him alive. This could be brimming with thematic meaning. Is this karma – a kind of cosmic justice by the natural world? Does the octopus represent Bond – a predator higher on the food chain than the pitiful Smythe? While these can still be debated, reading the actual text there’s so little exploration or insight into the event, it lacks an emotional punch, that one gets the sense Fleming was just concerned with the surface details. I was left thinking ‘what was the point of this story?’ It was close to being more but Octopussy is ultimately, and simply, the story of a man who gets eaten by an octopus.

The Property of a Lady.

The last few Fleming novels have moved away from the formula of the early James Bond adventures so, as one of the final stories, it’s quite nice to have it embraced once more. Bond is bored in his office reading documents relating to cyanide gas pistols – a fun connection to the opening of The Man with the Golden Gun – when he receives a call to visit M and have a classic briefing scene full of exposition, this time given by Jewellery expert Dr. Fanshawe. The scene is so epitomic of Fleming’s way of setting up his narratives, from the almost meta grumpiness of M having to sit through a meeting, the out-of-nowhere homophobia towards the cravat-wearing Dr Fanshawe, and the excessive detailing of the plot, which in this case involves the auctioning of Faberge’s missing masterpiece, the Emerald Sphere. The issue is that this scene isn’t condensed to more aptly fit a 40-page story and instead takes up half the total pages to bulk up the word count.

The Property of a Lady tries its damnedest to be a proper James Bond story yet doesn’t quite manage it. To understand it, one has to look at the circumstances under which it was written. Essentially, it was a puff piece commissioned by Sotheby’s, the auction house, to appear in their annual journal, and once I discovered that it was all I could see. The setting is Sotheby’s itself and at one point Bond reads the magazine the story would be published in and sickeningly praises its prose. The story is an advertisement first and a thriller a very distant second. Fleming even sucks up to the owner of Sotheby’s and mentions that the real-life auctioneer Peter Wilson is a “slim good-looking” man. It’s like if Goldfinger was interrupted by Bond mentioning his love of Audible to Pussy Galore and giving her a discount code to get a free audiobook on him.

There is, just about, a reason for Bond to visit the auction: the sale of the egg is to be payment for a known Soviet spy who is fed false information by the Secret Service. The mole is Maria Freudenstein and while the story is very much about her, she barely appears. As a double agent inside MI6, she is potentially a fascinating character, and the best moment is when Bond briefly meets her. “Bond’s skin crawled minutely at this proximity to treachery and at the black and deadly secret locked up beneath the frilly white blouse.” Bond having to deal with a Soviet agent who sits at a desk near his, and his thoughts on the matter, could have made for a good short story but it is barely touched on. Freudenstein’s motivations are also glossed over: “It was a common neurotic pattern – the revenge of the ugly duckling on society.” She’s ugly and flat chested and that’s why people become communists, according to Fleming.

At the auction, Bond is to identify an underbidder trying to jack up the price of the Faberge egg because they are likely to be another Soviet agent. Why he can’t just ask the auctioneer who is bidding I don’t know but Bond and ally jeweller Kenneth Snowman are able to check for tells on those in the room and spot the Soviet spy, who is tracked back to the consulate and the story concludes. Mr Snowman is too good a name to waste in this short story but I do enjoy seeing the wider elements of spycraft in Fleming’s world, which rarely appear in the novels. There are agents posing as photographers and taxi drivers to create a net around the enemy spy, although that does mean that Bond is more or less useless in the story. He’s usually a lone operator and while he does spot the baddie, so does another agent so even if Bond hadn’t been there the outcome would have been no different.

So, The Property of a Lady is a James Bond story where James Bond is useless, the one interesting element is ignored, and it never transcends its commissioned origin as a fancy advert for an auction house that feels far too real world to be exciting. It’s not just me who was disappointed by the final product but Ian Fleming himself too. He found it so lacklustre that he refused to accept payment for it and it was only published in paperback after his death.

The Living Daylights.

“This was to be murder.” That is Bond’s response to his latest assignment from M, an assignment he clearly doesn’t like yet begrudgingly accepts. Bond’s attitude to killing is explored throughout Fleming’s canon and yet it may be The Living Daylights that best concentrates it into something tough and tangible. While Bond claims to be fine with the idea, his actions prove otherwise as he drives angrily, honking at family saloons and skidding at roundabouts, revealing his true thoughts. The Living Daylights has a classic spy story set-up. It’s a video game mission before there were such things. Bond is to travel to Berlin and use a sniper rifle to protect a fellow agent who is crossing from east to west and take out the mysterious Soviet sniper known as ‘Trigger’. It’s a perfect mission to fit a short story format.

Finally, we get a James Bond story set in Cold War-era Berlin. I’m shocked it took this long to get an adventure set in Germany considering the potential it offers, and I would have taken an entire novel rather than just a short story. The location has such a strong sense of atmosphere, from the rubble and weeds to the glum buildings; I could almost hear the classical music Fleming mentions is playing while reading. It’s the perfect place for Bond to moodily hang around, debating whether to go for a walk or visit a brothel to distract himself from his mission. This is Bond perhaps at his most dark and disturbed with the pressure building, knowing he will take a life in a few hours.

People always say Timothy Dalton’s Bond feels most like Fleming’s creation, and while I think that varies book-to-book and isn’t as simple as some say, the Bond here is absolutely reminiscent of Dalton. Except at the beginning of the story where his conversations about cars and guns with someone at the firing range reek of Alan Partridge. And while moody Bond is one of my favourite Bonds, him chewing gum just feels wrong somehow.

Bond is forced to work with a spotter on this assignment, a Captain Paul Sender, who is described as “a sober, careful man [who] needed to chaperon Bond on this ugly business.” Sender is used as a comparative figure for Bond’s outlook but I question if Fleming takes this too far. Bond was never completely strait-laced but The Living Daylights paints him more as a bad boy, sick of working with ‘a square’. Yet Bond in the early books was a civil servant more than a badass action hero, which makes this an interesting story to end with. Did Fleming lose track of the character, him becoming more of the rogue action hero like the films, or is this change very much intentional, with Bond forever altered by his assignments since Casino Royale? I’m not totally sure but I’m leaning towards a bit of both. Apparently, M has sent him on “a hundred assignments” like this even though in earlier books Bond claimed he only had one or two a year. It has been fascinating seeing Fleming slowly strip the realism from the early books more and more just to continue the series.

Across the theatre of conflict, Bond begins a “long-range, one-sided romance” with a cellist he falls in love with, watching her as she enters and exits a building across the border, night-after-night. Honestly, this is one of my favourite romances from the series despite it not actually being one. Bond deluding himself into loving an unknown woman just to create an outlet for his misery during the mission is a great idea. Of course, the twist is that the cellist is ‘Trigger’ and Bond’s counterpart professionally rather than romantically. It’s obvious to the reader but the reveal still works. Bond can’t bring himself to kill her so shoots her weapon instead, hurting her hand and ending her career, and maybe his too.

“With any luck it’ll cost me my double-O number,” Bond muses, desperately wanting to get out of this life. I have to presume the story is set before On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and it makes that already brilliant novel even better by further establishing Bond’s headspace. I loved The Living Daylights. It’s a bright spot in a weak collection of stories and so very potent in atmosphere and mood. It’s one of Fleming’s best Bond stories, short or otherwise.

007 in New York.

Ian Fleming’s James Bond ends not with a bang but with a whimper. The final story is not a story at all, and, like The Property of a Lady, requires an explanation rather than an introduction. Fleming had written an article entitled “The Shame of New York” which, as you can imagine, was very unkind about the city. When the article was to be published in the US as part of his travel book “Thrilling Cities,” the publishers wanted to also include a (very) short story featuring Bond in New York to appease the American readership. The result was 007 in New York.

The Bond stories have always flirted with the travelogue so, as disappointing and dull as it is, 007 in New York being the final piece of Fleming’s Bond fiction almost feels correct. It sees Bond travel across the city while reflecting on how it has changed since his first experiences there. To call it a ‘short story’ is incorrect, it is only one of those two things. What little story there is is interrupted at one point by a recipe for scrambled eggs. It’s a hodgepodge of random thoughts and opinions, more Fleming’s than Bond’s, that the author was forced to write and therefore it is hard to critique in the same manner as the other stories.

Given the reason for the story’s existence, I was expecting an apology of sorts from Fleming, a brighter view of New York than his original article, but instead Fleming doubles down. 007 in New York is a troll job. The publishers wanted him to write Bond enjoying New York to sell books. Well, he’ll write a story of Bond in New York alright but the character certainly won’t be enjoying it. Fleming writes that “everyone looked wretched and undignified” and the first thing Bond sees is a man planning to rob arrivals in the airport. The whole story – all 8 pages – has a ‘back in my day’ attitude with Bond complaining about the influx of “hideous souvenir shops” and the poor state of the restaurants. This would normally irritate me but I enjoy the sheer bravado of Fleming essentially sticking his middle finger up to the publishers.

Surprisingly, a couple of elements found in 007 in New York were used in the Daniel Craig era films. Bond plans to spend the night with a woman named Solange, a name used for Casino Royale. Oddly, he was planning to take her to a porno theatre and sadist bar, the only good things New York has to offer apparently. Perhaps the most shocking thing Ian Fleming ever wrote is “as with the transvestite places in Paris and Berlin, it would be fun to go and have a look.” And, the single plot element of the story, that Bond is there to warn a former secret service operative that her new lover is an enemy spy, was used for the ending of Quantum of Solace. The story ends with the girl crying and threatening suicide; what a wonderful advertisement for New York.

Conclusion.

Octopussy and The Living Daylights is a lacklustre finale for Ian Fleming’s James Bond. It’s very clear why the title only mentions two of the stories: the other two are only included for completion’s sake and are barely stories. Before beginning the book, the idea that I only had four James Bond short stories left to read before it was all over was disappointing. The revelation that I actually only had two was heartbreaking. Of those Octopussy is an interesting read with some good characterisation but it feels repetitive and doesn’t quite come together. Blessedly, The Living Daylights exists and is the best of all Fleming’s short stories, and better than many of his novels for that matter. It’s an engrossing and insightful read, dark and gritty in a way that best encapsulates literary Bond. It proves there was still steam left in the series, still things left to learn about Bond, and Fleming still capable of excellence. I’m grateful for it but it only makes the pain of this as an ending even greater. Whether you count Octopussy and The Living Daylights or The Man with the Golden Gun as Fleming’s finale, neither – in their totality – are befitting of that status.

But while this is an end, it is not the end…

Stay tuned to OutofLives for my thoughts on the first James Bond continuation novel, Colonel Sun, written by Kingsley Amis in the coming weeks.