A page into Colonel Sun and Kingsley Amis, writing under his pen name of Robert Markham, is already describing what James Bond had for lunch and how awful London has become with its new architecture and disgusting modernisation. Just like that Ian Fleming’s creation continues as if the creator and author of the original fourteen books never died, the series as obsessed with fine dining and as grumpy about societal change as ever. I had never read any of Amis’s work before and was curious how a writer would tackle taking on Fleming’s famous literary figure in the very first continuation novel. The transition turned out to be smooth with Amis capturing not only James Bond but Fleming’s style too, possibly even surpassing it. Yet he still brings his own sensibilities to Bond, some which fit more than others.

‘Continuation novel’ is the correct and proper term for what Colonel Sun is but ‘fan fiction’ could also be applied. That is not to do the novel a disservice, it is simply what it is. This book is very much written from a fan’s perspective and this shines through from time to time, yet what pushes the novel past any potential pitfalls is that Amis is a writer who can unquestionably pull it off because his prose is incredibly strong. It’s maybe not as punchy and pithy as Fleming but is certainly poetic and intense. Amis clearly has some elements of the Bond canon he wanted Fleming to explore but now he’s able to do so instead, and I share the interest in them. Throughout the novels Bond describes Bill Tanner as his best friend yet it never feels like it, they don’t spend time together, whereas Colonel Sun immediately finds them golfing together and finally sells their relationship.

We catch up with Bond a year after The Man with the Golden Gun where he’s becoming a creature of habit, living a boring routine of office work and golf. “My existence is falling into a pattern. I must find some way of breaking out of it.” He looks at the other golfers and claims “the thought of becoming indistinguishable from them was suddenly repugnant.” I thought for sure this would be the starting place for a character journey or arc for Bond, giving us further insight into his thoughts on work and his addiction to it. But this is all we get on the matter and the character work for Bond is relegated to mere snatches throughout. James Bond feels like James Bond, which is perhaps all we need for the first novel without Fleming, to prove it is possible, but while Amis captures the character, he doesn’t add much to him. Bond’s routine is less character-focused and more to simply set up that he can now be easily followed…

Unlike many of Fleming’s novels, we don’t have to wait long for a burst of action. Given Colonel Sun was published in 1969, six films into the cinematic adaptation, I have to wonder whether the film series was beginning to have an effect on the writing of the books, with readers now demanding the faster pace they were used to from the big screen version. Bond and M are attacked at M’s home, Quarterdeck, and the baddies seek to kidnap them for some nefarious purpose. During this fight Bond is reminiscent of Sherlock Holmes, taking in lots of information in a microsecond, time seemingly slowing down for precise punches and descriptions of his adrenal glands firing. Bond manages to escape but M is kidnapped. It’s shocking and upsetting to see M, the elderly, fatherly man behind the desk, in danger like this. His capture is the inciting incident of the plot and while this is now well-trodden ground in the films, where the character is involved too much too often, this was a unique plot development at the time.

A clue left at Quarterdeck acts as a lure to get Bond to Greece. Bond knows it is a trap but has no choice but to spring it, hoping to find M before it is too late. In Athens he is approached by Ariadne Alexandrou, with Amis seemingly graduating from the Stan Lee school of alliterative names. Don’t get me started on the appallingly named Ranald Rideout. Ariadne is obviously an enemy spy from the very start but, while she’s a key character for the rest of the novel, it’s during this time of lying to Bond that the characters spend the most time together and talk, which is disappointing. Because she is pretending to be someone else, we don’t get to know the real her straight away. I didn’t know whether to let the information we learn here inform my view of her or not and that made her inscrutable for too much of the book. I was always expecting a twist or double cross even though, once finishing the novel, I realised that wasn’t Amis’s intention.

Ariadne’s defining trait is that she’s a communist and Amis doesn’t pull any punches when discussing real world politics, much more in line with early Fleming than the SPECTRE-dominated later years. I like this aspect of the character, her idealism, that Bond tries to challenge throughout the book. Bond suggests Ariadne has her political outlook because she is embittered by her moneyed youth and this is an outlet to rebel. Kingsley Amis himself was a communist in his youth but then grew increasingly right wing as he got older, a cliché but true. The author uses Ariadne to comment on this thinking, on his thinking. It’s almost as if Bond was, and will remain, a mouthpiece for Fleming’s views and so Amis instead uses Ariadne as a surrogate for his young self.

When Ariadne finally comes clean and she and Bond have to work together – a third party being behind the kidnapping, not the Soviets – they fall in love incredibly quickly. I’m willing to go along with it however because I always love the concept of enemy agents forming a taboo relationship, like in The Spy Who Loved Me film. I do take issue with Bond stating about Ariadne that he felt “more longing than he could remember feeling towards any other woman.” I know each Bond girl fights to be more desirable than the last but Bond not even mentioning his dead wife Tracy goes too far for me, even though she attracts Bond initially by discussing the “decreasing Greekness of Greece,” which is exactly his sort of conversation. Ariadne is also much younger than Bond and this often leads to relationships feeling awkward and lecherous, especially in the later Roger Moore films, but in Colonel Sun the age difference is important. She knows of war but was too young to fight in it, doesn’t truly know its horrors, while the older Bond has a different outlook, further informing their relationship.

It’s at this point in the novel, with Bond and Ariadne wining and dining and sightseeing, that differences between Amis and Fleming rise to the surface. Firstly, characters in Colonel Sun have actual back-and-forth conversations with each other. They converse naturalistically, even interrupting each other. A flaw of Fleming is that he could never be bothered to do this. His characters talked in monologues, multiple questions asked at once, each question then responded to in an equally long monologue, as if they were sending letters to each other. Yet Fleming was clearly as capable a travel writer as he was an author of thrillers. This is where Amis flounders, either not being as well-travelled as Fleming or just worse at communicating a sense of location and atmosphere. He focuses more on landmarks and architecture.

A second kidnapping attempt on Bond is thwarted when he is taken in by local Soviet intelligence who are then promptly murdered and Bond and Ariadne have to escape together, enemy agents in love, cut off from their respective agencies, solving the problem alone, trusting no one because there’s a mole in their midst. It’s almost like a purposefully confounding Coen Brothers plot at times, with multiple sides playing off each other rather than the usual simple goodies and baddies. Fleming didn’t deal in twists and turns. His plots were very straightforward and he had a desire for everything to be somewhat believable. Amis is not like that at all. There are sudden unexpected deaths and lots of action. Every spy trope Fleming didn’t use is somewhere in Colonel Sun. It’s great fun but so stuffed with ideas that many are left underexplored. There’s missed potential everywhere. Fleming’s stories were often spread too thin but for Amis the opposite is true. M’s kidnap should be a massive deal and the book easily could, and perhaps should, have explored Bond’s relationship with his boss/surrogate father, but that ends up being just one small part of the overall tale that is only sporadically mentioned.

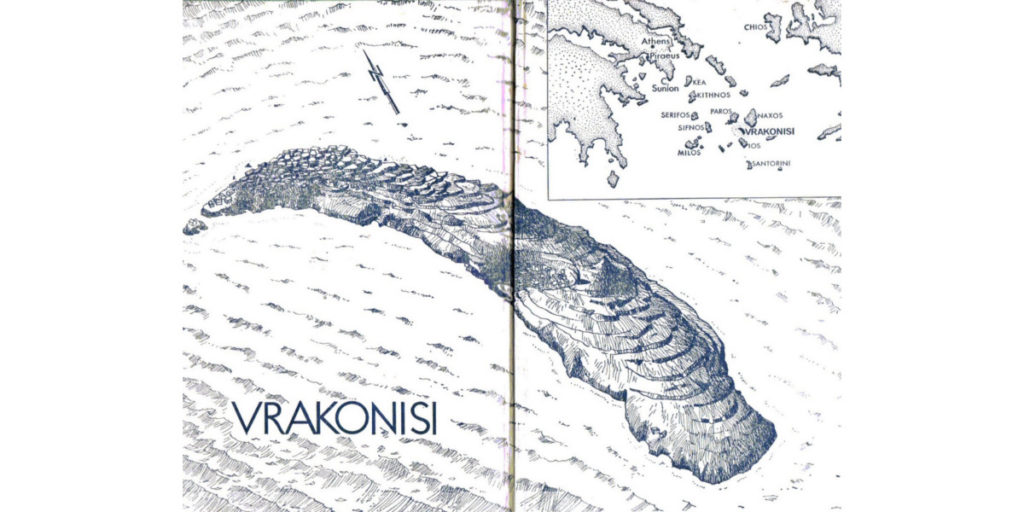

The rest of the novel takes place on and around the fictional Greek island of Vrakonisi, which is sickle-shaped in a very unsubtle link to the communist dealings that occur there. It’s here where the plot slows drastically and Bond is joined by Niko Litsas, the usual loudmouthed but likable and capable local who Bond attracts on every adventure. I like Niko but he becomes Bond’s main ally and Ariadne is demoted to second fiddle, doing little but having sex with Bond once a chapter. It turns out the island is host to a secret meeting between Russia and several Mediterranean and African nations which the villainous and eponymous Colonel Sun will attack with mortar fire and pin on Britain, leaving M and Bond’s bodies to be discovered and construed as the attackers. Bond makes sense, being he’s a secret agent and all, but frail old M taking part in an operation himself? Surely anyone could see through that falsity? Ariadne tells the Russian in charge of the meeting what is happening but he refuses to listen because, and this is Amis’s reasoning, he’s gay, with a penchant for young boys, and hates women. The spirit of Fleming’s homophobia, this time conflated with paedophilia and misogyny, lives on through Amis it seems.

Interrupting this abeyance of pace, Bond’s boat is attacked by Sun’s goons. Ariadne proves herself to be by far the most capable Bond girl of the novels, much more so than any woman written by Fleming. Not only does she kill an adversary but so too does teenage deckhand Yanni. While Amis is content with just writing Bond as a steadfast character, it’s here where he threatens to offer fresh understanding. “He had to get used to the idea of involving innocent outsiders in the kind of savage, unpredictable violence he traded in, but to have brought about the initiation of an adolescent into the ways of killing was something new to him.” It’s one of the most interesting parts of the novel and I would have loved for it to be further explored, but just like the book could have been about Bond’s relationship with M, but isn’t, or Bond’s relationship with an enemy agent, but isn’t, it isn’t really about Bond and Yanni either. Bond leaves the boy on a nearby island, refusing to take him further, worried he would be damaged, mentally and physically. It’s something new for Bond, perhaps even hinting at his own painful youth, but it feels like another tease of insight rather than the real thing.

While on a reconnoitre of Sun’s compound, Bond is held at gunpoint by a Russian who in turn is suddenly shot by Niko. “His eyes held Bond’s with a dreadful look of puzzlement, of pleading to be told how this thing could have happened.” I love this moment. It’s darkly comedic but heartbreaking too. Amis regularly finds way to humanise all his characters, however minor and despite their allegiance. He does something similar by dedicating an entire chapter to George Ionides, the man who swaps boats with Bond and ends up paying the price. It’s a sad chapter, learning of his life and desire for a woman’s hand in marriage before he’s brutally killed. George is just a man caught in Bond’s wake, an almost Fargo-esque unexpected consequence, a piece of human detritus. Yet I couldn’t help but chuckle at his demise. He gleefully waves at the people coming to kill him because he doesn’t know any better. I much prefer Amis’s sense of humour to Fleming’s and George’s chapter might be my favourite of the book.

Colonel Sun appears a couple of times throughout the novel before the big final confrontation with Bond but each time he did I abstained from taking notes. Even now in this review I’ve been putting off talking about him because, for most of the novel, I had no idea what to make of him. For the longest time I had no opinion of Sun. Colonel Sun Liang-tan of the People’s Liberation Army has a manner Amis describes as “bland politeness”. Bland is not a word I want associated with a Bond villain. Everything he does is “impassive” or “benign.” A calm and precise villain, such as Doctor No, is a Bond trope but they still need a certain arch outrageousness to be interesting. Without that aspect Sun is more of a Star Trek Vulcan, more interested in statistics than people, and he’s, quite simply, boring. I was expecting Sun to have a past with M and an interesting dynamic between the two but no, there’s nothing gained from pairing them together. One of Sun’s lackeys is an ex-S.S. officer called Von Richter, who is much more engaging. He’s an atrocity expert who killed hundreds of civilians during the war – a real detestable villain who should have been combined with Sun to make a great antagonist.

Thankfully, the big moment Sun’s appearance has been building to delivers and transforms the character into something monstrous. It literally does. Sun tortures Bond in a chapter that was excruciating to read; Amis matching Fleming in the ability to convey pain. The torture scene makes Sun interesting by shedding his previous boring personality and presenting torture as an intimate act between the two men. Sun is asexual but torture is his sex. It changes him, makes him animalistic, and a character even remarks “he’s not human.” The torture itself is like a Saw movie; the scene inspired by it in SPECTRE doesn’t do it justice. It’s not clinical in any way but messy and brutal as Sun stabs Bond, pushing long skewers and brush needles into his ears and nose to damage the brain. Just thinking about it makes me feels ill. Bond is completely helpless and Sun perhaps the most victorious villain of the books until, lamely, his asexuality is presented as his downfall. He tries to go all Ramsey Snow on Bond and have a naked woman arouse him during the torture, using Bond’s sexuality as a punishment while Sun’s asexuality is treated as an evil trait.

Instead, the woman frees Bond who manages to stab Sun with a skewer, beginning what is easily the most brutal and bloody finale to a James Bond story I’ve ever experienced. Having been introduced to Bond as a young child, I never want the Bond films to become excessively violent or supersede their status as bizarre family viewing, but I have to admit that reading a Bond story go all-out R-rated 18+ was great fun. I think it’s better than any action finale Fleming ever wrote. It’s fast-paced but never rushes like so many of Fleming’s. It’s so visceral too. Bond has to navigate a small house, barge his way into rooms and stab the occupants to death without making a noise as he searches for Ariadne, Niko, and M. It’s a huge change from the early Fleming adventures like Casino Royale where the height of action was Bond kicking someone to no effect.

After the blistering action finale, the final wrap-up chapter is a little more disappointing. The ending focuses more on the political ramifications of Bond’s mission rather than personal. With Sun’s plan scuppered and exposed, the relationship between Britain and the Soviet Union is galvanised and strengthened as a result. It’s all smiles and handshakes in a hotel lobby and I don’t buy it. A year ago, the KGB brainwashed Bond to assassinate M but that’s all been forgotten about apparently. I do like that Ariadne remains a G.R.U operative however. She’s not won over by Bond despite their feelings for each other. They realise they can’t be together, their love is politically taboo, but they end with a mutual respect as lovers but also as soldiers for opposing sides. M however fades away into the background and I wish there’d been a strong final moment with him and Bond. After being the catalyst for the plot, nothing came of him or his relationship with his best agent. A true missed opportunity.

With Colonel Sun, Kingsley Amis stayed true to Ian Fleming’s creation and writing while also taking James Bond up a notch. Not in terms of depth or quality, the novel is packed with character beats and plot threads begging to be further examined, but rather the sensibilities of the series. It’s a Fleming novel taken to the extreme – more unbelievable as a political thriller, much more violent, and even much funnier, with a particularly dark sense of humour that I loved. It’s a well-written novel and respectful to Fleming, perhaps too much in terms of James Bond himself. Amis truly captures the character but it feels like he’s scared to do much with him. Yet, for a first continuation novel, perhaps that is all it needed to do: prove that James Bond could exist beyond his creator. Colonel Sun is a worthy addition to the wider Bond canon, better than several of Fleming’s own works, and shows that Bond could not only survive continuations, adaptations, and reinventions, but thrive for years to come.

With Colonel Sun my James Bond odyssey comes to an end. The 15-part journey is complete and I now have a much richer understanding of the character’s literary origins and growth. Want to discuss book-bound James Bond? Let me know in the comments and be sure to geek out with me about TV, movies, and video-games on Twitter @kylebrrtt.